Global hunger is now at overwhelming levels around the world.

Earlier this month, a report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation for the United Nations found that more than 820 million people were deeply affected by hunger in 2021.

COVID had a major impact, spiralling by about 150 million people since the outbreak. The Ukraine conflict is exacerbating the situation.

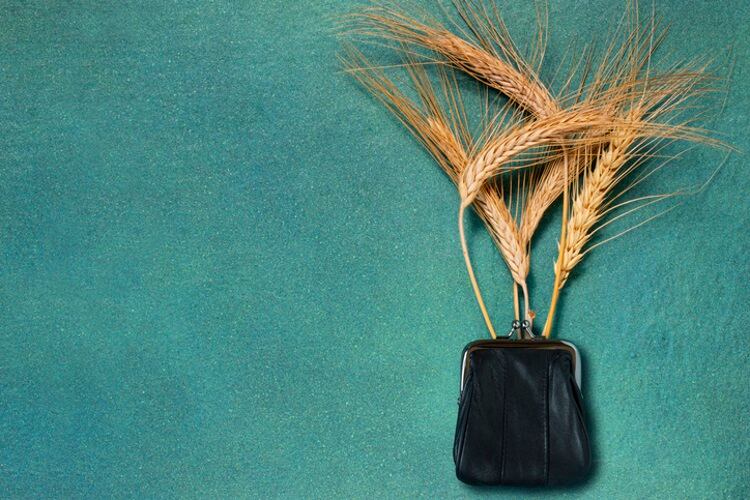

A broken food system

However, according to Hanna Saarinen, Oxfam Food Policy lead, the cause is not a shortage of food, but “a consequence of a broken food system further undermined by conflicts, the effects of the COVID pandemic and worsening climate change.

“It is easy to just blame today’s food crisis on the war in Ukraine, but longstanding political failure to address how we feed all the people in the world has made our food system susceptible to fragility and failure well before now.”

Prof Sayed Azam-Ali, OBE, CEO of Crops For the Future UK (CFFUK), concurs, noting in an opinion piece in the Financial Times that “supply chain disruptions, a pandemic, extreme weather and now a war in Ukraine have exposed fault-lines in the global food system that we ignore at our peril.”

Climate change, in particular, threatens almost everything when it comes to food. More than 40% of wheat on America’s great plains is suffering from drought, while floods in China mean wheat yields this year will be among the poorest ever. Europe is in the grip of a deadly heatwave; the UK reach a record 40.3°C on 19 July; and India registered record temperatures of 49°C in May.

Prof Azam-Ali advocates “nothing less than a complete transformation of agrifood – one that involves diversifying the crops we grow, the way we grow them and how we transport them.”

Breach of 'beacon of hope'

Literally hours after shaking hands in agreement to open Black Sea shipment routes to export the 22m tonnes of wheat, corn and other grain sitting in Ukrainian silos and about to rot, Russia carried out a strike on the port of Odesa.

The grain export agreement was signed in Istanbul under the auspices of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres Guterres, along with Ukrainian and Russian delegations – and is critically important for global food security.

As many as 47 million people are at risk of acute hunger because of the conflict, according to the World Food Programme. The deal will particularly help 45 African countries that import a majority of their wheat from Ukraine or Russia, including Burkina Faso, Egypt, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.

Thankfully, despite the breach, Ukraine officials said preparations are still under way to resume the grain exports. But the aggression puts the grain deal – described as a ‘beacon of hope’ by Guterres – in the balance, the first major agreement struck between the two sides in the five-month conflict.

Urgent rethink

Even if Ukraine grain trade is restarted, a massive logistical effort will need to be carried out to move all the millions of tonnes of it before it stales and continues its wrecking ball punch on global food prices and poverty levels.

Cereal prices reached a peak in May, falling 4.1% in June. However, they remain 27.6% higher than last year. In the case of wheat, prices fell 5.7%, but still remain 48.5% higher than in June 2021. The FAO reported that cereal demand is outpacing supply for the first time in four years – and production continues to fall globally.

Countries like Uganda have long been swapping out alternatives to wheat – such as cassava and yam – but CFFUK’s Prof Azam-Ali said a global-wide strategy is needed to introduce climate-resilient and nutritious ‘forgotten’ crops, especially if we need to “nourish a predicted 10 billion by 2050 on a hotter planet.”

Man has cultivated around 7,000 plant species as crops, of which, just three – wheat, rice and maize – provide over 60% of the human diet. The remaining 40% is divided between creating biofuels, feeding pigs and cows.

The salient points of his future food vision:

- Stop feeding food crops to animals and engines.

- Use all landscapes – urban spaces, common land and even gardens – as food sources.

- Diversify systems from regimented monocultures to provide greater resilience to extreme climates and potential livelihoods for a new generation of farmers.

- Embrace food as a source of cultural value and joy, not just a means of sustenance and source of profits.

“The Global Manifesto on Forgotten Foods, launched in 2021, calls for a plan of action in which forgotten foods, from climate-resilient and nutritious crops such as fonio and bambara groundnut, can become agents of transformation,” writes Prof Azam-Ali.

“We must rediscover local, nutritious and diverse foods and reduce our addiction to a monotonous diet of uniform, ultra-processed products that are transported around the world.

“This requires vision, investment, a scientific knowledge base and farmers as innovation partners, not passive recipients of new technologies.

“In growing forgotten crops in a changing climate, it is they, not us, who are the experts. Producers and consumers, not companies, must lead the urgent rethink of the food system for the good of humanity and the planet.”

Oxfam’s Saarinen’s advice is more targeted and fingers the custodians of the world’s food system.

In a 6 July statement published in reaction to the FAO’s 2021 food insecurity report, Saarinen said the collective wealth of today’s ‘food billionaires’ has reached ‘stratospheric’ levels – “increasing by $382bn just over the past two years.”

She calls for a new, more just and sustainable global food system that serves the planet and millions of people, rather than a handful of big agribusinesses.

“Western governments must free up resources – including by taxing food companies and billionaires – in order to invest in diverse, local sustainable food production that helps countries to become less dependent on food imports; and support smallholder food producers, especially women,” said Saarinen.

“To save lives now, rich donor governments must honour their promised funding pledges. East Africa, which is witnessing its worst drought in recent history and where over 28 million people are facing extreme hunger, and thousands are already starving, has received less than 15% of its nearly $7 billion UN humanitarian appeal to date.”

Dismal progress towards 2030 Agenda

The FAO’s stark message in The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022: Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable highlights the disappointing progress we’ve made since the 2030 Agenda was launched in 2015, indicating that policies need a dramatic overhaul.

According to the report, despite hopes food security would begin to improve after COVID, world hunger rose further in 2021.

The prevalence of undernourishment jumped from 8% to 9.8% between 2019 and 2021, with between 702 and 828 million people affected by hunger in 2021 (150 million since the outbreak of the pandemic).

Projections are that nearly 670 million people will still be facing hunger in 2030 – 8% of the world population – back to 2015 levels.

Severe food insecurity rose higher in 2021 reflecting a deteriorating situation for people already facing serious hardships. Around 2.3 billion people were food insecure in 2021, but a shocking 11.7% faced food insecurity at severe levels.

In 2020, around 22% of children under five years of age were stunted and 6.7% were wasted – typically from rural areas and poorer households – while 5.7% were overweight – usually from urban areas and wealthier households.

Almost 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet in 2020; 112 million more than in 2019, reflecting the inflation in consumer food prices stemming from the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and measures put in place to contain it.

The FAO noted these setbacks reveal that policies are no longer delivering increasing marginal returns in reducing hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms, and that it is now time for governments to start examining their current support to food and agriculture.

The UN agency calls for repurposing of support (the concept of upcycling has actually become quite fashionable in the bakery and snacks sectors).

According to the report, repurposing existing public support will help increase the availability of nutritious foods, and more importantly, contribute to making healthy diets less costly and more affordable all over the world.

It must be done smartly and informed by evidence, though, involving all stakeholders, keeping in mind countries’ political economies and institutional capabilities, and considering commitments and flexibilities under World Trade Organisation rules.

Policymakers must avoid potential inequality trade-offs in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and constraints on farmers, especially in lower income countries where agriculture is key for the economy, jobs and livelihoods.

This, said the FAO, is crucial to bridge productivity gaps in the production of nutritious foods and enable income generation to improve the affordability of healthy diets – although it will require significant development financing.

The price of bread

But we’re still a long way off towards this ideal, so it’s essential that Ukraine’s grain is released to ease the suffering of millions in need around the globe.

Officials said Ukraine could export 60 million tonnes of grain over the next nine months, but it would take up to 24 months if its ports were disrupted.

David Miliband, CEO of the International Rescue Committee, said in a statement, “For 12 hours, we dared to hope for relief of the global hunger crisis from shipments of Ukrainian grain. We have said it before; the war in Ukraine is a tragedy for Ukraine but also a global disaster for those in greatest need. This latest twist is as cruel as it is dangerous.”

Bread-flation, too, is banking on the ‘beacon of hope’ deal.

Amid the highest US inflation in four decades, bread prices has jumped into sticker-shock territory at an unheard of $10+ a loaf: a scenario that is seeing identical implications around the globe.

Which begs the question: How long can consumer demand hold up amid such inflation?

According to NielsenIQ data, cracks are beginning to show and shoppers are skipping the bread aisle, with unit purchases from US grocers in the year to 2 July declining by 2.7%.

And what about the industry itself?

The $50bn US bread industry was already facing the challenge of shifting consumer tastes (IBISWorld), and now, just as bread is gaining back its reputation, the dramatic price hike could usher in another carb-cutting boom.

Experts warn of more volatility ahead in wheat and bread prices – likely to last well into next year, if not longer.