It may be a small seed the but Singapore-headquartered supplier Olam is banking on big growth in the global sesame seed market, which is already worth $8bn (€6.8bn).

The rise of fast food outlets in Asia – primarily India and China – will be the biggest driver over the coming years. And while a sprinkling of sesame on a burger bun may not seem much, the sheer size of Asia's burgeoning middle-class populations means large volumes.

Parallel to this is the growth of health and wellness foods hitting Western shelves, and sesame is well-positioned to tap into this trend too.

The hummus section in supermarkets offers an increasing number of flavours while tahini is used as a healthy alternative to mayonnaise in salads or to replace or reduce dairy fats in ice cream. Whole sesame seeds are added to breads, muesli or used in gomasio, a Japanese condiment that blends crushed sesame seeds, sea salt and seaweed flakes to replace table-top salt.

Around 70% of global production is crushed for sesame oil, while around 15% goes towards tahini (sesame paste) and a further 15% is used as a food ingredient, such as bread and bagel toppings or in muesli.

Speaking to FoodNavigator at the company's processing plant on the Black Sea coast in Turkey, general manager Swaroopanand Joshi said: “There has been a complete change in perception. Five years ago, I don’t think anyone would have guessed sesame would be such a big culinary trend.”

“Going forward, the most important thing we are seeing is the corporate entry into [products containing sesame]. In the past three to five years, Nestle and PepsiCo have entered the hummus market and Unilever is marketing an ice cream with tahini. That’s why it makes sense for Olam to have tahini in its portfolio. We don’t want to compete with small tahini processors to serve the local market here [in Turkey] but the big giants.”

“The open sesame moment is coming,” he added.

In fact, demand is growing at such a pace that suppliers are struggling to keep up. Olam is currently doubling the capacity of its processing plants in Samsun, Turkey and around Lagos in Nigeria but further expansion may be necessary, Joshi said.

“Logically it would probably make sense to expand here [in Turkey] and add one more line to the existing plant but we don’t have a presence yet on the other side of the Atlantic and that region is growing so that would also make sense.”

Different needs, different seeds

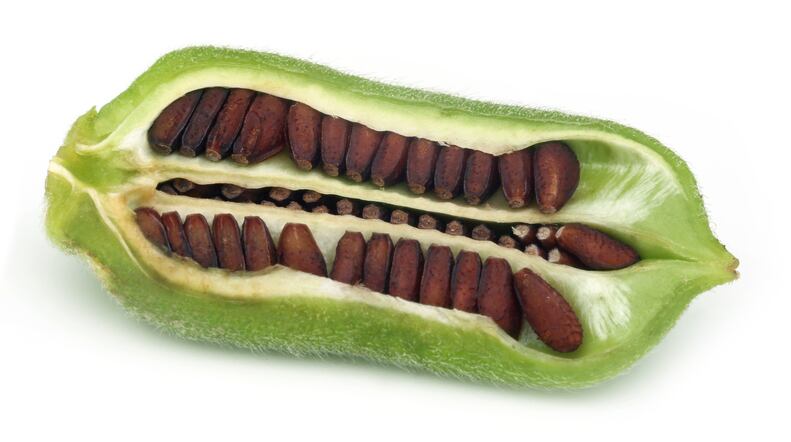

Depending on the variety, sesame seeds contain around 50% oil, 25% protein and 10% fibre.

There are around 40 varieties, each with a distinct flavour profile, and Olam trades numerous varieties. This mixed portfolio sourced from various countries mean it can answer customer demand around the world.

For instance, fast food outlets such as McDonalds and KFC want flat sesame seeds that stick to the buns while manufacturers of simit, a Turkish bagel eaten for breakfast, want seeds to be as small as possible to cover more surface area.

Chinese manufacturers tend to prefer Nigerian sesame because of the high oil content – sesame oil is used in Chinese cooking for shallow frying – while Turkish customers prefer Ethiopian seeds because the higher protein content gives a sweeter taste, Joshi said.

A presence in Africa and the Mediterranean

China and India used to provide the world’s sesame seeds but, in the past ten years, both countries have been encouraging farmers to switch to higher value crops such as cotton or staple food crops such as corn and soy.

Previously a net exporter, China now imports sesame to meet its needs while Indian output has fallen from around 900,000 to 200,000 tonnes. Today seven of the top ten producer countries are in Africa.

According to FAOSTAT data, the top ten producer countries in 2014 were Tanzania, India, Sudan, China, Myanmar, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Chad and South Sudan.

Each year Olam buys around 250,000 MT of sesame from one million farmers and intermediary sellers. The location of its two processing factories give the supplier a proximity to sesame’s sourcing and to the end market.

“Africa is where sesame is grown but not where it is eaten. Turkey gives us quick, easy access to the market – Turkey, Greece, Lebanon, Israel, North Africa. They all use tahini in traditional foods.”

Price volatility

By buying sesame from producers based in many different countries, Olam can weather the supply disruptions that come with “any supply chain concentrated in Africa”, Joshi said.

Sesame has an annual price volatility of around 25 to 30%, and this is mainly due to “sovereign” supply issues rather than crop failures. Recent problems include a road closure blocking access to Nigeria’s port and a currency crisis in Sudan meaning farmers are withholding stocks.

However, this price volatility tends not to affect manufacturers of baked products so much as they use seeds in such small quantities, Joshi said.

The move to mechanisation

Sesame seeds have a dark outer shell and must be dehulled before use. The traditional method is to soak the seeds in water until the skin is loosened, and then rub them to remove the skin. It’s a water intensive method that uses around 3000 litres of water per metric tonne.

The mechanised process used by Olam in its Nigerian and Turkish factories, known as aqua hulling, sprays the seeds with high-pressure water jets to remove the skin and uses just 150 litres per metric tonne.

“The problem is that most of the processing is happening in developing nations where sensitivity to water usage is still not there. [Mechanised] processes make much more sense,” Joshi said, adding that the organoleptic properties suffer.

“With soaking, water is absorbed to the inner core so when you dry and roast it, the taste is slightly different – the aroma is much better due to the conversion of fats to proteins and protein to sugar, which is much better.”

“With mechanical hulling the taste might not be that good but for bakery or hummus – where it is only a tiny percentage of the total product – it doesn’t matter.”

Some customers do specify they want tahini made from traditionally hulled sesame seeds for a richer taste profile but this is falling. “Slowly the world is understanding that mechanical processing is more sustainable and this trend will follow.”