Key takeaways:

- Most of the easy salt reductions are already done, leaving food makers facing technical, quality and safety limits rather than quick reformulation wins.

- Policy pressure is rising globally, but sodium reduction looks very different in practice across bakery, dairy, ready meals and beverages.

- Without clearer regulatory roadmaps, manufacturers risk being caught between public health ambition and the realities of how food is made.

The recent headline that Britons consume the salt equivalent of 22 packets of potato chips (crisps) a day is doing exactly what it’s meant to do: provoke alarm. What it doesn’t do is explain why, after decades of reformulation, sodium has become one of the most stubborn nutrients left in the food system.

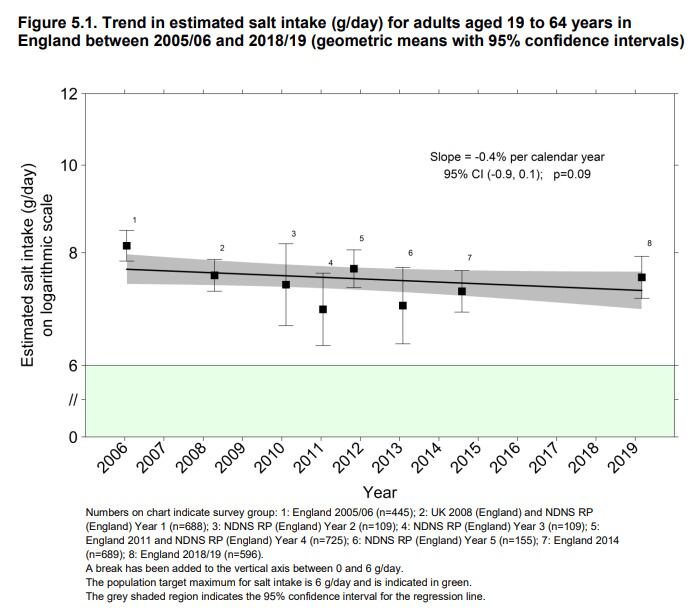

Data released by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) shows working-age adults in England consume an average of 8.4g of salt a day, well above the UK’s 6g guideline. The health implications are well known: high salt intake is linked to elevated blood pressure, which increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

On that basis, the BHF is pushing for mandatory salt targets to be embedded in the UK Government’s forthcoming Healthy Food Standard. From a public health perspective, the argument remains the same: voluntary action has slowed and stronger levers are needed.

Manufacturers don’t deny the health risks associated with excess salt. What they’re questioning is whether policymakers are underestimating how far reformulation has already gone. The large, relatively straightforward reductions are largely in the rear-view mirror. What remains is smaller, harder and far more sensitive to product quality, safety and cost.

That tension isn’t unique to the UK. Average salt intake remains above recommendations set by the World Health Organization across Europe, North America and much of Asia, including in markets that have spent years pursuing sodium reduction. The UK debate is one expression of a much wider problem: how to push further without breaking the foods people actually buy.

What’s the UK’s Healthy Food Standard?

The Healthy Food Standard is a proposed UK policy designed to change what people buy by changing what large food businesses sell overall.

Rather than setting product-by-product reformulation rules, the Standard is expected to require large retailers and food businesses to report on the nutritional profile of their sales, using nutrient profiling models that account for salt, sugar, saturated fat and calories. Over time, those businesses would be expected to increase the share of healthier products sold.

The framework has been shaped by research from Nesta, a UK-based innovation and policy body focused on long-term social challenges, including diet-related ill health. Nesta has argued that shifting sales patterns is more effective than banning or reformulating individual products in isolation.

Companies would retain flexibility over how they respond, whether through reformulation, range changes, promotions, pricing or product placement.

The Healthy Food Standard sits within the Government’s 10-Year Health Plan, announced in June 2025. Th full plan is expected later this year, with consultation likely in the second half of 2026. A phased rollout from 2027 is expected, beginning with mandatory reporting before any binding targets are introduced.

Although aimed at retailers, the Standard is expected to influence reformulation priorities and commercial decisions across the supply chain.

Bread and the limits of salt reduction

If there’s one category that illustrates both progress and constraint, it’s bread. Bread contributes a significant share of dietary salt, largely because it’s eaten daily. At the same time, it’s one of the areas where sustained reformulation has already delivered substantial reductions.

Andrew Pyne, chief executive of the Federation of Bakers (FoB), says that progress is often missing from the conversation. “The UK has one of the lowest salt levels in bread globally,” he says. “Over the past decades, the Federation of Bakers’ members have helped the plant bread and bakery industry achieve a 30% reduction in salt, to below 1g per 100g of bread.”

Most white breads now sit firmly in green traffic-light territory for salt. Even so, bakery continues to be described as a source of ‘hidden’ sodium. “As well as clearly labeling the amount of salt in wrapped bread, we challenge the often-made claims bakery contains hidden salt,” Pyne says.

What’s left, he argues, isn’t reluctance but reality. “There are limits to salt reduction due to the technical functionality of salt in bread, and there needs to be an understanding that not all food sectors can further reduce or remove salt.”

Salt affects dough strength, fermentation, texture, shelf life and food safety. Strip too much out and quality suffers. Shelf life shortens. Waste increases. Costs rise. Those trade-offs are hard to capture in headline statistics.

The same problem shows up elsewhere

Bakery isn’t an exception. The same constraints exist across other food categories. In cheese, salt is central to structure, microbial control and maturation. In soups, sauces and ready meals, it underpins preservation and flavor delivery, particularly as clean label expectations reduce the availability of functional substitutes. These aren’t optional roles; they’re fundamental.

The BHF’s findings are based on urinary sodium data from the 2018-19 National Diet and Nutrition Survey, carried out by Public Health England. Comparable studies in Europe and North America point in the same direction. Early reformulation delivered meaningful gains. Subsequent reductions have been slower, costlier and far more constrained.

Beverages, too, are being pulled into the debate. Sports drinks, functional beverages, broths and meal replacements are increasingly scrutinized as sodium labeling tightens and nutrient profiling systems expand.

Policy pressure, uneven pathways

Consumer understanding hasn’t kept pace with policy ambition. Polling by the BHF and YouGov shows many people struggle to estimate their salt intake or recall official guidelines. Confusion between the UK’s 6g recommendation and the WHO’s 5g benchmark is common and not confined to Britain.

That leaves manufacturers in an awkward position. Products can meet existing targets and still attract criticism as sodium becomes lumped in with sugar, fat and ultra-processed foods (UPFs) in broader health debates.

In the US, the policy landscape is looser but no less complicated. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has favored voluntary sodium reduction guidance, labeling and education over binding limits. Draft sodium targets exist, but uptake is uneven and timelines remain flexible. For manufacturers, expectations are shaped as much by retailers and litigation risk as by federal policy.

Pyne argues that any next phase of regulation needs to start from where industry actually is. “FoB members committed to helping people reduce the salt in their diets by making significant reductions over the last few decades following investments in innovation,” he says. “We hope the government will work with industry sectors and recognize the investment and progress that have already been made. They must provide the regulatory certainty and support needed for any future regulations.”

That challenge isn’t going away. Governments can keep tightening sodium targets in isolation or they can broaden the conversation to look at dietary patterns as a whole. Either way, the path ahead is unlikely to be neat. And while snack foods make easy villains, the real strain is falling on staple categories that can’t simply be reformulated out of existence.