Key takeaways:

- Weight regain after stopping GLP-1 drugs is rapid and common, with many consumers returning to pre-treatment weight and risk markers within just a few years.

- As millions cycle off GLP-1s, appetite often returns faster than confidence, creating a fragile moment where food choices are shaped as much by fear as by hunger.

- Food makers now face a pivotal choice: help stabilize eating habits and nutrition during the post-GLP-1 transition or risk reinforcing anxiety and disordered behavior through overly restrictive or medicalized cues.

As millions quit GLP-1 drugs and weight rebounds faster than expected, food makers face rising pressure around nutrition, trust and mental health.

For a while, GLP-1 weight-loss drugs looked like a reset button. Appetites faded. Meals became smaller, less frequent, sometimes optional. Some users even talked openly about forgetting to eat altogether. For parts of the food industry, especially categories built on routine and pleasure, it was unsettling to watch.

That phase didn’t last.

What’s becoming clearer is something less dramatic, but much harder to manage. Large numbers of people are stopping GLP-1 drugs, some by choice, others because of side effects, cost or simple exhaustion. Hunger returns quickly. Weight usually follows. Confidence around food often doesn’t.

People eat again, but not always comfortably. And increasingly, not without fear.

When GLP-1 stops, weight returns faster than expected

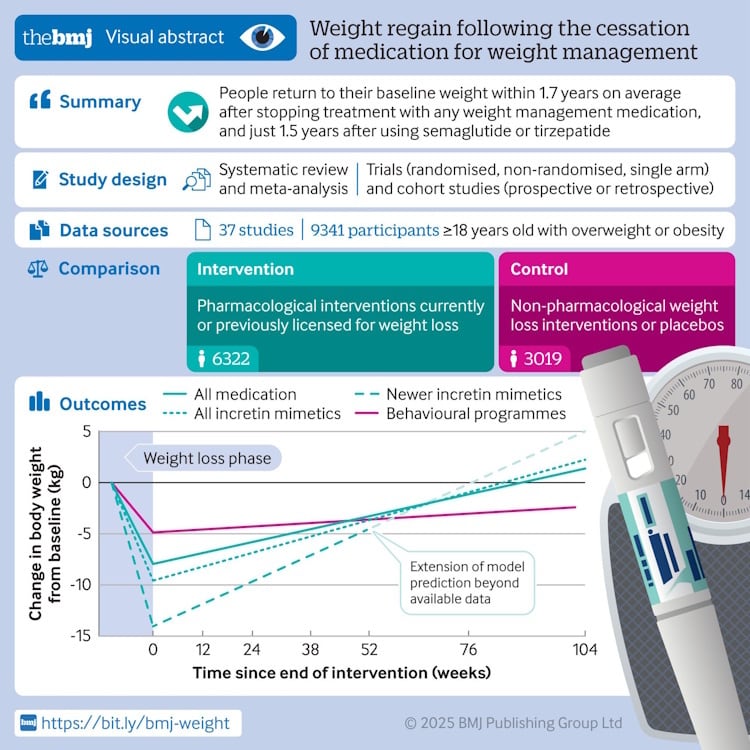

The most comprehensive evidence so far comes from a large meta-analysis in The BMJ. Researchers from the University of Oxford, led by postdoctoral researcher Sam West, examined 37 clinical studies published up to February 2025, involving more than 9,000 participants who had taken obesity medications, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, for an average of 39 weeks.

The findings were stark. After treatment stopped, participants regained weight at an average rate of around 0.9lb (0.4kg) per month. At that pace, the researchers estimated that body weight would return to pre-treatment levels in less than two years. More concerning, improvements in cholesterol, blood pressure and diabetes risk reversed within around 1.4 years.

As the authors noted, “indirect comparisons showed that people regained weight faster after stopping weight-management medications compared with behavioral weight-management programs, regardless of how much weight was lost during treatment.”

Global GLP-1 disruption webinar

Weight-loss jabs are reshaping food and drink markets worldwide, altering consumer behavior and forcing brands to rethink product development, portioning and positioning. But the impact is uneven – what’s playing out in soft drinks or alcohol doesn’t always translate directly to snacks, confectionery or dairy.

FoodNavigator’s upcoming Global GLP-1 Disruption webinar, airing February 5, 2026 at 3pm GMT/10am EST, will examine how GLP-1 medications are influencing different categories, where disruption is already visible and where expectations may be running ahead of reality.

The session will explore category-specific responses, emerging formulation strategies and how companies are adapting to shifting consumption patterns tied to appetite suppression and weight management.

Hosted by Nicholas Robinson, global audience & content editor at FoodNavigator, the panel will feature speakers from Lifesum, the Institute of Food Technologists, Circana, Rousselot, and Beneo, alongside editors Gill Hyslop (Bakery&Snacks), Rachel Arthur (BeverageDaily) and Teodora Lyubomirova (DairyReporter).

The researchers were clear in their discussion. While GLP-1 drugs are effective at inducing weight loss, obesity remains a chronic condition that’s difficult to manage long term, and weight regain is common once treatment ends without sustained dietary and lifestyle support.

In other words, appetite suppression is temporary. Eating behavior isn’t.

People are quitting GLP-1s and their habits don’t reset overnight

This isn’t a marginal cohort. Polling conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation in November 2024 found that around 12% of US adults said they were currently taking a GLP-1 drug, while roughly 18% reported having taken one at some point. That equates to tens of millions of consumers who have already cycled through appetite suppression.

Discontinuation is common and rising. A large 2025 study in JAMA, tracking more than 125,000 patients, found that nearly 47% of people with type 2 diabetes stopped taking their prescribed GLP-1 within a year. Among people using the drugs without diabetes, discontinuation rose to around 65%.

Crucially, many don’t restart. Real-world datasets suggest that for weight-loss users in particular, stopping often marks the end of treatment rather than a pause. Cost, side effects and long-term tolerability all play a role.

From a food perspective, this creates a large and fast-growing post-GLP-1 cohort. Insights from Lumina Intelligence show that GLP-1 use has reshaped eating patterns in ways that don’t simply disappear when medication stops. Users tend to eat fewer meals, gravitate toward smaller portions and seek foods that feel functional, satiating or ‘safe’.

Once appetite suppression quiets so-called ‘food noise’, expectations around fullness and portioning shift, particularly for long-term users. When appetite returns, caution often doesn’t fade at the same pace.

The elephant in the room: a brewing eating-disorder risk

This is where the conversation becomes uncomfortable. Clinicians working in eating-disorder treatment say the post-GLP-1 phase deserves far more scrutiny than it’s currently getting.

GLP-1 drugs don’t cause eating disorders. But specialists report relapses among patients who had been stable for years after exposure to the drugs. The risk lies in the overlap between appetite suppression, rapid weight loss and a cultural environment that’s once again celebrating thinness.

Celebrity use has amplified that pressure. High-profile admissions and visible transformations from figures such as Oprah Winfrey and Kelly Clarkson, combined with relentless social media commentary, have reframed dramatic weight loss as both aspirational and medically sanctioned. For individuals vulnerable to disordered eating, that combination can be combustible.

Clinicians describe a familiar pattern. People come off GLP-1s. Hunger returns before trust does. Weight gain feels like failure. Eating more feels risky. For some, anxiety about stopping medication becomes as powerful as the appetite suppression itself.

Food sits right in the middle of that moment.

These pressures place new responsibility on food makers. As Ed Sibley, commercial director at Lumina, told NutraIngredients, “as the GLP-1 category scales, nutrition brands have a unique window to establish credibility and trust by aligning with the evolving needs of these consumers.”

What matters here isn’t novelty or claims. It’s defined by whether brands can help stabilize eating habits at a moment when many consumers are actively unlearning how to eat without fear.

Rather than chasing users with ‘GLP-1 friendly’ labels, the bigger challenge is counterbalancing anxiety.

That means products that quietly support micronutrient intake after rapid weight loss, including iron, calcium, B vitamins and vitamin D. It means paying attention to texture, moisture and digestibility, not just macros. It means portion sizes that feel complete rather than corrective. And it means language that avoids control, discipline and moral judgment.

Handled well, food can help people relearn how to eat without fear. Handled poorly, it risks reinforcing the very anxieties that GLP-1s have exposed rather than resolved. The difference won’t come down to protein grams or portion sizes alone, but to whether the industry treats this moment as a nutritional transition, not another diet cycle.

Designing for the post-GLP-1 consumer

The post-GLP-1 consumer isn’t defined by medication, but by transition. These are people finding their way back to eating after prolonged appetite suppression.

Micronutrient density matters more than ever. Rapid weight loss is linked to deficiencies in iron, calcium, vitamin D and B vitamins, particularly among women and older adults. Products that support adequacy without medicalized claims can help stabilize intake.

Digestive tolerance deserves attention. Texture, moisture, acidity and fat composition influence whether foods feel approachable during and after GLP-1 use. Comfort often determines repeat eating.

Portion size is a design decision, not a moral signal. Smaller formats work when they feel complete and satisfying, not corrective. Visual cues, resealability and pacing matter.

Language carries risk. Messaging built around control, discipline or ‘permission’ can slide straight into diet culture. This is especially relevant as meals and snacks labeled ‘GLP-1 friendly’ become more common in US supermarkets, despite the absence of FDA regulation for the term. Framing around nourishment, energy, balance and everyday eating tends to build trust over time.

A simple test helps clarify positioning: would this product still make sense if GLP-1s disappeared tomorrow? If not, it’s probably too narrow to last.

Sources:

Sam West, et al. Weight regain after cessation of medication for weight management: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2026;392:e085304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2025-085304

Mailhac A, et al. Discontinuation of semaglutide therapy for weight loss: population-based study of the first 77,310 users in Denmark. EASD 2025, abstract 681.

Patricia J. Rodriguez, et al. Discontinuation and Reinitiation of Dual-Labeled GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Among US Adults With Overweight or Obesity. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8;(1):e2457349. https://doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.57349