Key takeaways:

- Many UK snack bars marketed as healthy contain surprisingly high levels of free sugar, often rivaling confectionery.

- Action on Salt & Sugar argues that voluntary labeling and weak regulation are enabling misleading health claims and slowing reformulation.

- The group is calling for mandatory front-of-pack labels, tighter rules on claims and levies to push the category toward genuinely healthier products.

For years, snack bars have ridden a wave of health-conscious marketing. Shoppers grab them for school bags, desk drawers, gym kits and glove compartments, reassured by claims like ‘no added sugar’ and ‘high in fiber’.

But a new nationwide survey from Action on Salt & Sugar shows the glow of virtue is purportedly masking something far less wholesome. Many of these bars deliver sugar and calories at levels that would surprise even the most label-savvy parent.

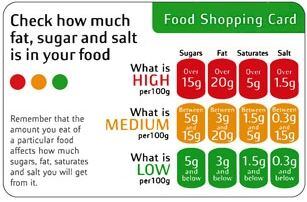

The headline figure is hard to ignore. When judged under Chile’s far tougher warning-label system, 68% of the ‘healthy’ bars sold in the UK would carry a high-in-sugar warning. Under Britain’s softer, voluntary traffic-light scheme, they mostly get a pass.

Dr Kawther Hashem, senior lecturer in Public Health Nutrition and head of Research and Impact at Action on Salt & Sugar at Queen Mary University of London, says this is a clear sign the system is outdated and too easy to game. “The UK’s current voluntary system is widely recognised and trusted by consumers, but more than 10 years on, it remains inconsistently applied and does not apply to food and drink sold out of home,” she says.

That inconsistency matters, especially when the average snack bar in the survey delivered 7 grams of sugar per serving – nearly a third of a young child’s maximum daily allowance for free sugars. Parents reaching for something that looks better-for-you are instead handing kids what Dr Hashem describes as a disguised sugar hit.

“We need a mandatory labelling system on all food and drink products to better inform consumers and drive reformulation,” she says. And critically, she adds, it should “be aligned with the latest public health recommendations on free sugars intake and be regularly reviewed against the latest global evidence base.”

Brands have learned that health-language sells. Shoppers are typically time-poor so front-of-pack claims do the heavy lifting. But Action on Salt & Sugar’s latest analysis shows just how often those claims obscure reality.

Bars touted as ‘no added sugar, ‘protein-packed’ or ‘high in fiber’ often contained high levels of free sugars. “Consumers are often faced with misleading claims on packaging, which create a ‘health halo’ effect, masking less favourable nutrient profiles,” says Dr Hashem. Her solution is simple: reserve such claims for genuinely healthy products. “Stronger regulation is needed to ensure that only genuinely healthier products can make such claims,” she says.

Snack bars have long fallen into a blurry zone between indulgence and health. Now that they’re part of children’s diets, Action on Salt & Sugar argues the stakes have changed. Many bars surveyed packed nearly a third of a child’s entire daily sugar limit yet were marketed as convenient nutrition boosters.

Dr Hashem says manufacturers have a clear and immediate responsibility. “Manufacturers have a significant responsibility to ensure these products are not exceeding high sugar thresholds and in the immediate term are not categorized as high in fat, salt and sugar according to the Nutrient Profile Model,” she says. In other words, brands shouldn’t be calling something a health snack while it sits in the same nutritional territory as confectionery.

A labeling system overdue for an overhaul

The UK’s traffic-light labeling scheme was once considered world-leading. But as other countries have moved toward more assertive, easier-to-understand warning labels, Britain has stayed still. Dr Hashem points out that even the government knows the system needs updating. “In 2020, the Government reviewed the front-of-pack nutrition labeling system via an open consultation but did not publish the outcome,” she says. With no revised policy and no mandate forcing consistent use, the system has drifted into irrelevance.

Clear, mandatory labels would do what the voluntary system no longer can: create consistency and nudge brands toward healthier formulations. “Clear color-coded or warning labels will ensure a level playing field, support informed consumer choice and encourage industry-wide reformulation.” Without them, assets Dr Hashem, the door stays open for healthwashing.

Why voluntary reductions haven’t worked

The UK once hoped that industry goodwill and gentle guidance would bring down sugar levels across major categories. But the voluntary sugar-reduction program aimed at a 20% reduction by 2020 delivered just 3.1% in biscuits and cereal bars. Dr Hashem says the results speak for themselves: voluntarism isn’t enough.

“We urge the Government to introduce targeted levies on food and drink high in fat, salt and sugars, including those sold out of home, building on the proven success of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy,” she says. The drinks levy famously drove widespread reformulation almost overnight. Dr Hashem believes the same would happen in snacks. “Such a levy would incentivize reformulation, shift purchasing behavior towards healthier options and generate revenue that could be reinvested into prevention, public health initiatives and equitable access to nutritious foods.”

And, she stresses, it would protect the companies already doing the right thing. “A levy would also level the playing field for responsible food businesses that have already taken steps to reduce unnecessary salt and sugar.” Today, these companies are effectively competing against rivals who haven’t bothered.

Protein bars: big market, loose rules, growing confusion

If any part of the snack bar world is ripe for regulatory clarity, it’s protein bars and energy-style bars. Their halo is even brighter: fitness positioning, high-protein claims and lifestyle marketing have created a sense of healthfulness that isn’t always backed by nutrition. Yet this booming segment sits in a gray zone that doesn’t clearly fall into the sugar-reduction program’s existing categories.

Dr Hashem says this needs fixing now. “Whilst mandatory reporting and target setting are in development, the Government should continue to instruct businesses to comply with the reformulation programs for salt, sugar and calories and add these categories to the most appropriate category within the current programs.” Right now, some manufacturers can simply sidestep guidance because the program doesn’t explicitly place them anywhere.

Where she wants the regulations to go next is more ambitious: transparency, accountability and standardization across the sector. “We strongly support the introduction of mandatory reporting on the healthiness of sales for food and drink businesses,” she says. But it must be meaningful, not a box ticking exercise. “Reporting must be comprehensive, across a wide range of food and drink, with a consistent set of indicators that capture nutrients of concern, particularly salt and sugars, as well as positive indicators such as fiber and fruit and vegetable sales.”

She also wants mandatory healthy sales targets that force progress. “Data should be transparent, comparable and allow for accountability across the sector.”

The watchdog’s new findings reveal a category that has drifted far from its ‘healthy’ image. The UK now faces a labeling system that hasn’t kept pace with global standards; voluntary reformulation programs that haven’t delivered meaningful change; and a marketplace where health claims are often louder than the nutrition beneath them.

Dr Hashem believes consumers deserve honesty and manufacturers shouldn’t be allowed to lean on marketing language that distracts from high levels of free sugars, fat or calories. Without mandatory labeling, clear rules on claims and strong incentives to reformulate, she warns the current cycle will continue – with children most at risk of long-term diet-related harm.

The study

Published to coincide with Sugar Awareness Week, the analysis examined 458 snack bars sold across 10 of the UK’s biggest supermarkets. Despite being marketed as ‘convenient’ and ‘nutritious’, the results showed huge variation in nutritional quality, with products ranging anywhere from 62 to 378 kcal in a single serving.

Using the UK’s traffic-light nutrition labeling system, the survey found that while 28% of bars were considered low in total sugars, the average serving still contained 7g of sugar – nearly two teaspoons and about one-third of a 7-10-year-old’s recommended daily free sugar limit. More than half the products (55%) were high in saturated fat. Among bars carrying a ‘high in fiber’ claim, 31% were also high in sugars.

Some individual products pushed the numbers even higher. M&S Dark Chocolate Date Bar contained 26.5g of sugar per serving (almost seven teaspoons), while Kellogg’s Rice Krispies Squares Caramel & Chocolate Snack Bar packed in 14g. Other high-sugar items included fruit and nut bars such as Nakd Salted Caramel and Nakd Blueberry Muffin, as well as cereal-based bars like Kellogg’s Rice Krispies Squares in multiple flavors and Lexi’s Strawberry Crispy Bar.

Protein-positioned products were no better. Myprotein Filled Wafer Hazelnut and Nakd Protein Peanut Butter ranked highly for sugars, while the Deliciously Ella Roasted Peanut Protein Ball delivered 16g per serving. By contrast, the lowest-sugar option identified was the Grenade Dark Chocolate Mint bar at just 0.4 g per serving.

Calories were equally variable, averaging 175 kcal across the full sample. The highest-calorie products were the Chia Charge Chia Seed Flapjack With Sea Salt Flakes at 378 kcal per serving, followed by the Banana version at 357 kcal and the H&B Ginger Flapjack at 347 kcal. The lowest was Skinny Crunch Light Salted Caramel at 62 kcal per serving.

* Product examples were based on per 100g to make direct and fair comparisons across products.