Key takeaways:

- The lawsuit argues that citric acid made via black mold fermentation shouldn’t be called ‘natural’ when used to boost flavor.

- Citric acid’s one of the most common additives in snacks and drinks, yet almost all of it now comes from fermentation, not fruit.

- The case could force brands to rethink ‘no artificial flavors’ claims as shoppers demand clearer definitions of natural.

PepsiCo and Frito-Lay have been hit with a class action over one of the most familiar ingredients in food: citric acid. It’s in practically everything – crisps, candy, baked goods, fizzy drinks. But according to the complaint, the version in Poppables isn’t what consumers think it is.

The lawsuit, filed in New York’s Eastern District, says the citric acid in Poppables is “manufactured using black mold,” despite the front of the pack stating ‘no artificial flavors’. The filing argues that this makes the label “categorically false.”

It’s a simple claim with big implications: can a flavor enhancer still be called ‘natural’ if it’s brewed in a fermentation vat instead of squeezed from citrus fruit?

From fruit grove to fermentation tank

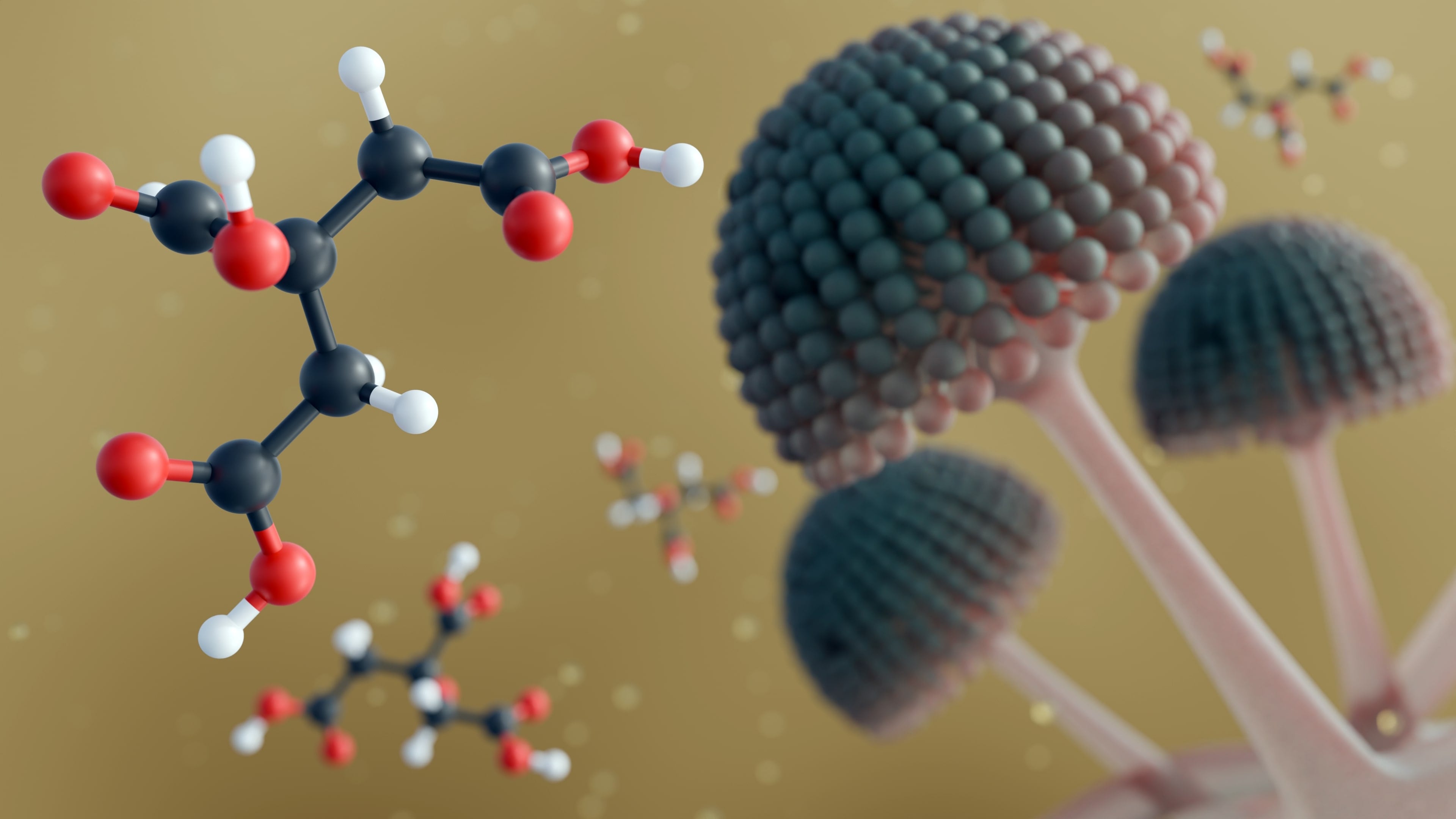

Most people assume citric acid comes from lemons. In reality, almost all of it is produced through industrial fermentation, using a strain of black mold called Aspergillus niger. The mold consumes sugar, releases citric acid and is filtered out before the ingredient’s added to foods. It’s cheap, efficient and has been standard practice for over a century.

The plaintiff, Staten Island resident Yovani Palmeri, argues that because this mold-made citric acid is added to Poppables for its sharp, tangy flavor – not just for preservation – it should be considered an artificial flavor.

“Consumers purchase snacks labeled ‘No Artificial Flavors’ precisely because they wish to avoid synthetic, chemical, or laboratory-generated compounds,” the lawsuit says.

Few consumers would ever guess that such a familiar ingredient starts with mold spores in a sugar vat. But in the age of clean label marketing, where ‘natural’ has become shorthand for ‘wholesome’, those details suddenly matter.

The black mold angle

The complaint goes further, painting Aspergillus niger as an allergen that “can cause adverse reactions in individuals with mold sensitivities.” It cites studies showing one in five people test positive to A. niger spores. It also mentions a 2018 toxicology study that found “potential inflammatory responses” to manufactured citric acid.

To be clear, there’s no suggestion that Poppables are unsafe. The lawsuit’s about transparency, not toxicity. The claim is that consumers were misled into paying more for something they believed was free from industrially made flavor compounds.

What is Aspergillus niger?

Aspergillus niger is a black mold species used in industrial fermentation since 1919 to make citric acid and enzymes. It breaks down sugar into citric acid in large fermentation vats.

The mold itself’s filtered out before the ingredient’s refined. While A. niger spores can cause allergies in environmental settings, the citric acid it produces is chemically identical to fruit-derived acid and approved globally for food use.

Palmeri’s lawyers argue that PepsiCo built an entire marketing platform around ‘natural’ snacking while relying on a mold-made molecule to achieve its signature zing.

PepsiCo and Frito-Lay haven’t commented, but its expected they will counter that citric acid is chemically identical whether it comes from lemons or mold and that under FDA definitions, it doesn’t count as an artificial flavor.

When ‘normal’ ingredients stop feeling natural

Citric acid’s long been one of food manufacturing’s quiet heroes – a go-to for balancing taste, brightening flavor and extending shelf life. It’s been used safely for more than a hundred years. Yet its origin story is awkward in a world obsessed with transparency.

That’s the tension this lawsuit taps into: how much do consumers actually want to know about how their food is made?

The clean label trend has blurred science and storytelling. Fermentation-based ingredients are increasingly common – not just for citric acid, but for flavorings, colors, even dairy proteins. They’re sustainable and scalable, but the moment a brand puts ‘no artificial flavors’ on the pack, it opens itself up to scrutiny.

The complaint describes the citric acid in Poppables as ‘industrial’ and ‘laboratory-produced’, arguing it doesn’t fit the plain-language understanding of ‘natural’. That phrasing may resonate with juries and consumers alike, even if regulators see things differently.

Clean label, messy definitions

The phrase ‘no artificial flavors’ has become one of the most powerful sales hooks in the snack aisle – and also one of the most dangerous. It’s widely used, loosely defined and easily challenged.

Under US law, whether a flavor counts as ‘artificial’ depends on its chemical structure, not how it’s made. But consumers don’t read regulations; they read packages. And for many, ‘made from mold’ doesn’t feel natural, even if the end compound’s the same as one found in citrus fruit.

That gray area’s become a growing legal battleground. Similar lawsuits have targeted beverage makers for using fermented citric acid while claiming ‘natural flavors’. Others have gone after snacks for using synthetic versions of compounds found in fruit.

The Poppables case takes that argument one step further – spotlighting a common ingredient that’s quietly used across nearly every major food category. If a judge decides fermentation counts as artificial production, the ripple effect could reach across the whole packaged foods industry.

For brands chasing ‘clean’ positioning, the challenge isn’t just avoiding artificial additives – it’s deciding what counts as one in the first place.

The risk beyond the courtroom

Even if PepsiCo successfully defends the science, it can’t easily control the optics. ‘Mold-made molecule’ is a phrase that sticks. Once consumers picture that in their snacks, the damage is done.

The lawsuit’s a reminder that the clean label movement isn’t just about health; it’s about trust. And when scientific processes sound too industrial, even the safest ingredients can suddenly sound suspect.

In the end, the court will decide whether PepsiCo broke any labeling rules. But in the court of public opinion, this case’s already opened a conversation that’s been brewing quietly in R&D labs for years: how do you explain modern food science to consumers without making it sound unnatural?

What counts as an ‘artificial flavor’?

According to FDA rules (21 CFR §101.22), a flavor’s artificial if it isn’t derived directly from a plant or animal but is made through synthesis or fermentation.

If a compound like citric acid’s used to boost flavor and made via fermentation instead of fruit extraction, some argue it’s artificial. But the FDA focuses on what the molecule is, not how it’s made – leaving plenty of gray space for lawsuits like this.

Case reference:

Palmeri v. PepsiCo, Inc. and Frito-Lay North America, Inc., Case No. 1:25-cv-05371-VMS, U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York. Filed September 25, 2025.

Studies:

Poulsen JS, Madsen AM, White JK, Nielsen JL. Physiological Responses of Aspergillus niger Challenged with Itraconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2021 May 18;65(6):e02549-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02549-20. PMID: 33820768; PMCID: PMC8316071.

Sweis IE, Cressey BC. Potential role of the common food additive manufactured citric acid in eliciting significant inflammatory reactions contributing to serious disease states: A series of four case reports. Toxicol Rep. 2018 Aug 9;5:808-812. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.08.002. PMID: 30128297; PMCID: PMC6097542.