Key takeaways:

- A University of Porto study found 27% of EU biscuits exceed the bloc’s acrylamide benchmark, putting consumer safety and brand trust at risk.

- Recipe choices – especially flour type, sweeteners and asparagine-rich add-ins – strongly influence acrylamide levels in biscuits.

- Industrial use of the enzyme asparaginase can slash acrylamide by up to 100% without altering product taste or texture.

Biscuits have always carried a wholesome image – a humble teatime staple, a toddler’s treat, a quick office snack. But research published online on September 25 in Journal of Food Composition and Analysis has blown the lid off that comfort: more than a quarter of biscuits on sale in Europe contain levels of acrylamide above recommended safety benchmarks.

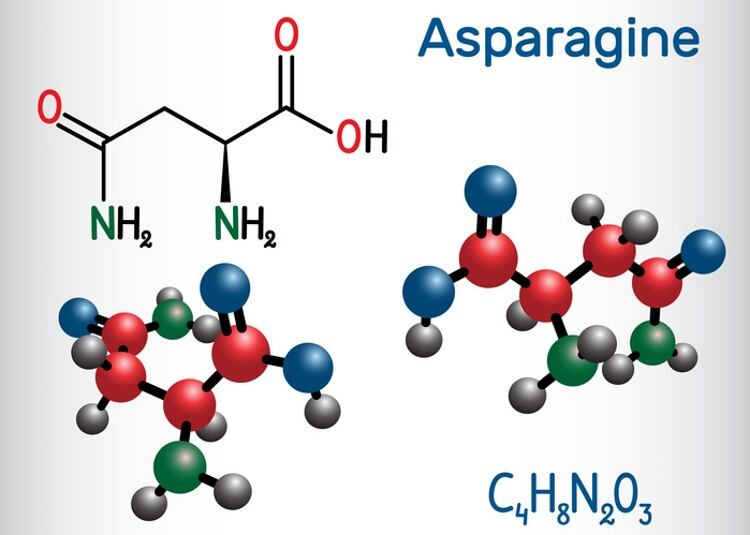

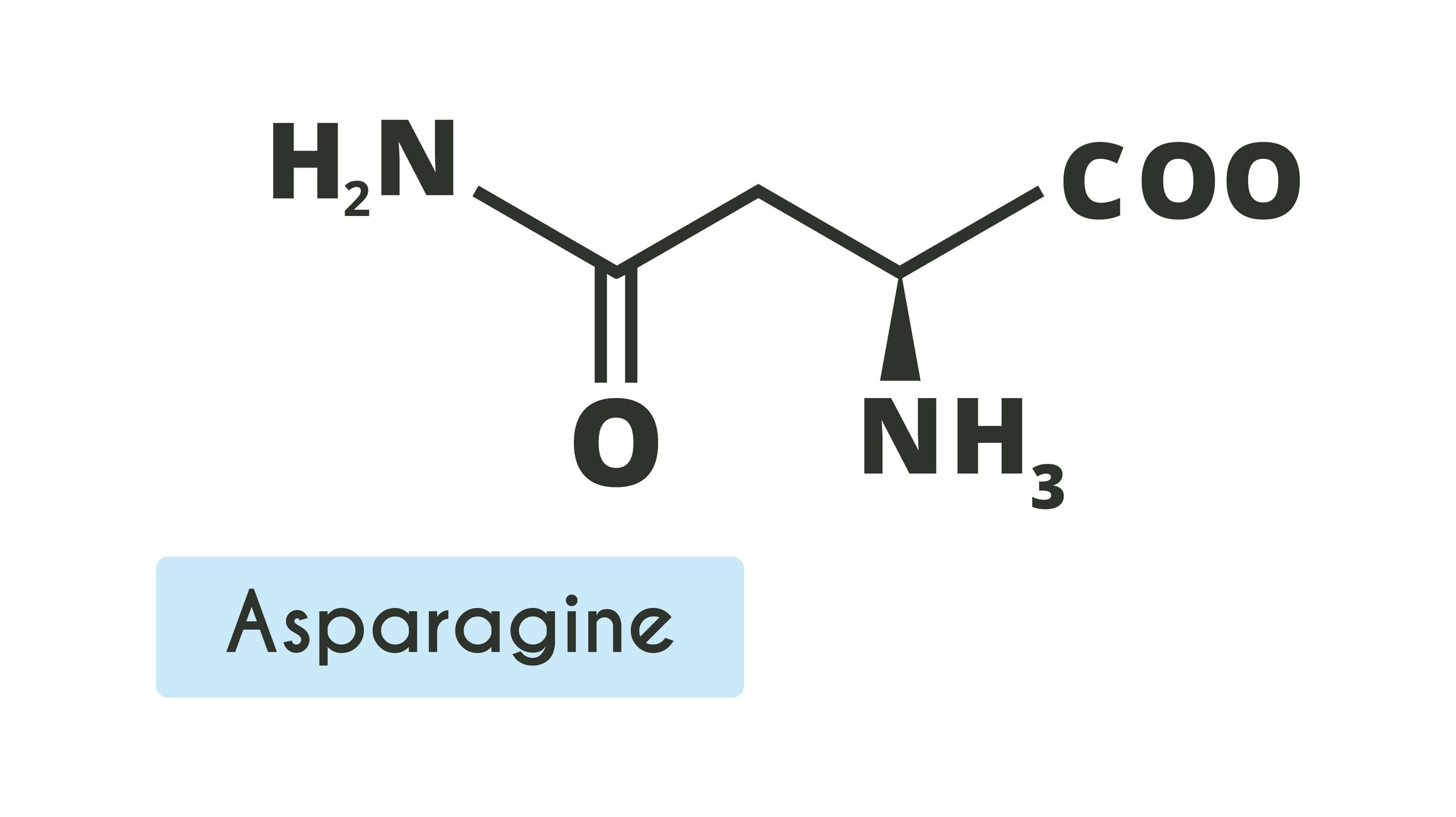

Acrylamide is the industry’s open secret. The chemical contaminant forms naturally when sugars and the amino acid asparagine react during high-temperature baking. It’s also a probable human carcinogen, classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer as Group 2A. Regulators have been tightening the screws for two decades, but the new study shows progress is patchy at best. Some biscuits contain no detectable acrylamide. Others clock in at dangerously high levels – and consumers have no way of knowing the difference.

The latest findings should rattle every player in the bakery and snack sector. Acrylamide isn’t just an abstract chemical problem. It’s a regulatory, reputational and consumer-trust problem.

Recipe roulette: How ingredients dictate risk

The study, led by Phd student João Siopa at the University of Porto, makes it clear why acrylamide levels vary so wildly. The culprit is dough composition. Acrylamide is born when free asparagine collides with reducing sugars during baking. The more of those precursors in the dough, the higher the finished biscuit’s acrylamide load.

The researchers found a near-perfect correlation between dough asparagine content and acrylamide levels (r = 0.943). Ingredients matter: apple powder, naturally high in asparagine, pushed biscuits into dangerous territory. Flours tell a similar story. Rye and oats typically generate higher acrylamide than rice or corn. Even wholemeal flour tends to spike levels compared with refined white flour.

Sugars play a pivotal role, too. Sucrose, the common table sugar, is non-reducing and produces lower acrylamide. Fructose or honey, on the other hand, are highly reactive. The difference isn’t subtle: recipes using sucrose consistently showed lower acrylamide levels than those relying on reducing sugars.

For manufacturers, this is both bad and good news. Bad, because recipe tweaks can make or break compliance. Good, because the levers are already in their hands. Choosing the right flours and sweeteners is a strategic decision.

Enzymes to the rescue

If ingredient choices are the first lever, enzymes are the second and they may be the industry’s closest thing to a silver bullet.

The Porto team tested industrial applications of asparaginase, an enzyme that degrades asparagine before the oven ever gets hot. The results were dramatic: acrylamide levels fell by 74% to 100%. In some biscuits, acrylamide all but disappeared.

Acrylamide 101

What it is: A chemical contaminant formed when asparagine reacts with sugars during high-temperature cooking.

Why it matters: Classified as a probable human carcinogen (IARC Group 2A) and genotoxic, meaning it can damage DNA.

Where it hides: Potato chips, French fries, coffee, bread crusts, breakfast cereals, biscuits, cookies.

Benchmarks: EU sets 350 µg/kg for biscuits, 150 µg/kg for baby biscuits. Proposed: tighter benchmarks plus a hard maximum.

Biggest risk group: Children, who consume proportionally more biscuits than adults.

Crucially, this was achieved without touching the recipe or the production line. That matters, because earlier attempts to mitigate acrylamide with acids, amino acids or plant extracts often altered taste, color or texture. Asparaginase works invisibly. The biscuit looks and tastes the same but it’s far safer.

Not every recipe responds equally. Biscuits made with apple powder still showed stubbornly high levels even after enzyme treatment, though reductions of around 75% are still impressive. For mainstream products, asparaginase is the most effective, market-ready fix available.

Regulators are losing patience

Europe has led the global crackdown since 2018, when it introduced binding regulation requiring levels of acrylamide to follow the ALARA (‘as low as reasonably achievable’) principle. For biscuits, that means a benchmark of 350 µg/kg. If a product overshoots, companies are obliged to review and improve their process.

But the bar is moving. Brussels is now weighing proposals to tighten the benchmark to 300 µg/kg and impose a hard maximum of 500 µg/kg. Go above that, and your biscuit could be banned from shelves.

Elsewhere, the rules are looser but no less risky. In the US, the FDA issues guidance rather than limits, but California’s Proposition 65 has triggered lawsuits over acrylamide, including against coffee brands. In Canada and Asia, regulators monitor and advise but stop short of strict caps. Japan has gone furthest in the region with a handbook guiding food makers on acrylamide reduction.

Brussels isn’t backing off – if anything, it’s tightening the screws. Regulators are done with polite suggestions. Consumer groups are vocal. And parents – who assume a biscuit is a safe snack for their child – aren’t likely to tolerate chemical caveats for much longer.

Global mitigation snapshot

Europe: Strict regulation since 2018, with tighter rules incoming. Enzymes widely adopted.

North America: FDA issues guidance; California’s Prop 65 lawsuits drive reformulation.

Asia-Pacific: Japan issues reduction handbook; China aligns with Codex. Industry adoption of enzymes growing.

Industry innovations: Enzyme solutions (asparaginase), low-asparagine grains, antioxidants, and optimized baking tech.

Crunch time

The biscuit aisle is facing a reckoning. The science is undeniable, the solutions are available and regulators are circling. Acrylamide may be formed naturally, but leaving it unchecked isn’t acceptable anymore.

The University of Porto study is a wake-up call: one in four biscuits still breach EU benchmarks, even as enzymes can erase the problem almost entirely. This isn’t just a food safety issue. It’s a question of brand trust, regulatory compliance and consumer confidence.

ALARA in action: Practical acrylamide fixes for craft bakers

Let's be honest, for a family bakery, the idea of testing for acrylamide might feel miles away from reality. But the Porto study shows there are some simple steps even small producers can take:

Start with flour. Rice and corn tend to carry less free asparagine than rye or oats. Wholemeal versions can push levels up, too.

Stick with table sugar. Sucrose doesn’t drive acrylamide in the same way as fructose, glucose or honey.

Watch your extras. Ingredients like apple powder or dried fruits are naturally high in asparagine. They taste great, but they can send acrylamide soaring.

Adjust the bake. Running a little cooler or pulling trays out a minute earlier won’t kill the biscuit but it may keep acrylamide lower.

Look at enzymes. Asparaginase isn’t only for the multinationals. Some suppliers now sell it in quantities small enough for craft bakers.

None of this guarantees compliance and testing is still the only way to know for sure. But it does show that keeping acrylamide in check isn’t just a big-industry game.

Study:

João Siopa, Miguel Ribeiro, Fernanda Cosme, Fernando M. Nunes. Survey of acrylamide in marketed biscuits and industrial mitigation via dough composition and asparaginase. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 2025, 108375, ISSN 0889-1575, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2025.108375