Key takeaways:

- Upcycling is starting to take hold in Africa’s food sector as bakeries and snack makers repurpose leftovers and offcuts.

- Finance, policy support and platforms like Standard Bank’s OneFarm Share are essential to scaling waste-reduction efforts.

- Surplus nuts, fruit and bakery byproducts are being turned into new snacks and cereals, proving waste can create value.

Bakers, snack makers and suppliers in Africa are slowly embracing upcycling as they search for ways to cut waste amid rising costs and supply chain uncertainties.

Global momentum is already building. Research by Allied Market Research valued the upcycled foods market at $53.7bn in 2021 and projects it to almost double within five years.

For Africa, adopting food waste reduction is especially critical, given the combined pressures of production economics, climate change and food insecurity. Stuart McClarty, president of the South African Bakers Association (SABA), said food manufacturers in Africa must also move quickly to catch up with global players like Nestlé and Mondelez, which have already embedded upcycling into their operations.

“It’s important to upcycle in food and snacks production, more so in the bakery industry here in South Africa and elsewhere across the continent,” said McClarty. “Any good bakery, for example, will turn a day-old cake into cake pops or something else that isn’t wasted.”

Local bakeries learning from global giants

Nestlé has begun working with farmers in Kenya, providing preservation systems that turn surplus fruit and vegetables into less perishable products. The challenge, McClarty added, is ensuring manufacturers properly manage offcuts so they can be reused instead of discarded. What cannot be reintegrated into food can often be sold into the livestock feed market, as seen in Zimbabwe and South Africa where pig and poultry farmers use bakery waste as feedstock.

Nestlé’s work with Kenyan farmers to cut food waste

The Swiss conglomerate has introduced simple preservation systems so that surplus fruit and vegetables last longer and can still be sold.

The move builds on the Nescafé Plan, which started in Kenya in 2011. That program has trained thousands of coffee farmers, supplied new seedlings and set up demo plots to reduce crop losses. More recently, Nestlé has added ‘agripreneurship’ workshops in counties such as Nyeri and Murang’a. Farmers are encouraged to grow extra crops like arrowroot or tree tomato and shown how to handle them better after harvest.

A nutrition component runs alongside. Through its Farmer Family Nutrition project, Nestlé promotes kitchen gardens and encourages families to use surplus produce in meals rather than let it spoil.

Finance and policy will unlock next phase

Banks are expected to play a key role in enabling wider adoption. Louis van Ravesteyn, head of agribusiness at Standard Bank, Africa’s largest bank by assets, headquartered in Johannesburg, said the lender had “noted various innovations over the years to reduce food waste, including vacuum and intelligent packaging, high-pressure processing and upcycling.

“It is, however, not just about food waste reduction, but also how we can utilize waste more efficiently in the food production value chain. For example, innovations linked to the circular economy approach, where producers re-purpose waste to generate energy through anaerobic digestion, are coming up,” he explained.

He added that “upcycling is gaining traction in Africa as farmers and food manufacturers recognize its potential to lower input costs, provide new revenue lines, improve margins” and enhance competitiveness.

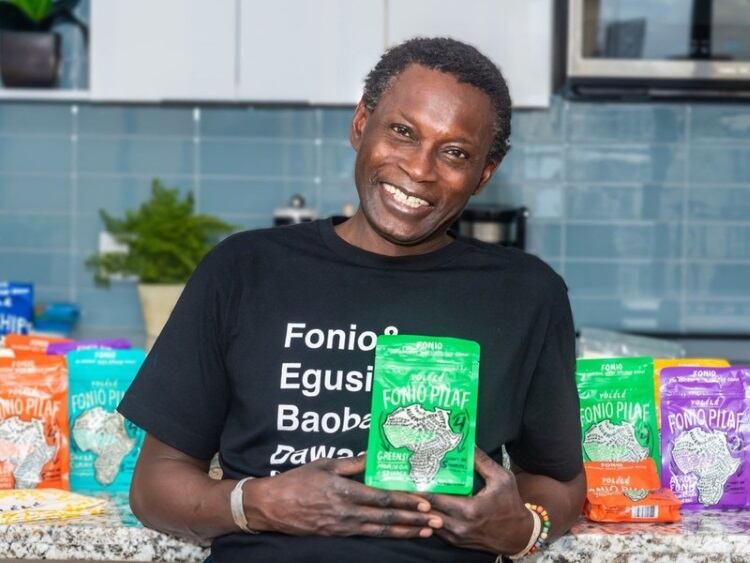

Still, Ravesteyn stressed that policy incentives, market development for upcycled products and investment in scalable technologies are needed to accelerate growth. Across the continent, practical models are already emerging: broken cashews are being absorbed into granola, snack bars and bakery lines in West and Southern Africa; oil-pressed peanut cake is reworked into Nigeria’s protein-rich kuli-kuli snack; and researchers are showing how groundnut and Bambara flours can be blended into cereals to lift protein and mineral content. Each example shows how surplus and by-products can be turned into value rather than loss.

Standard Bank is piloting solutions through its OneFarm initiative, which connects farmers with off-takers to ensure food surplus is redistributed rather than wasted. Since its launch, OneFarm Share has:

- Facilitated more than 114 million meals

- Redirected 28,700 tonnes of surplus produce

- Reached over 1.2 million people

- Engaged 743 contributors, from farmers to distributors

The initiative is currently focused on South Africa, working with partners such as FoodForward SA to handle cold-chain logistics and distribution. Standard Bank positions the project as both a food-security measure and a circular-economy model, proving that efficiency gains can come from better coordination rather than new supply.

Training, however, is as important as investment, stressed SABA’s McClarty. “We have to understand it (upcycling) and look at it as a necessity for the industry.

“It’s not just at the corporate leadership level but on the ground – the chefs, the trainees, everyone across the bakery value chain; we all need to be trained on how to reuse and repurpose food from the production processes,” he said.