Key takeaways:

- Longer fermentation in Europe helps break down gluten and FODMAPs, making bread feel easier to digest.

- EU rules ban additives still allowed in the US, leading to cleaner labels and shorter ingredient lists.

- Europeans buy fresh bread daily, while Americans rely on packaged loaves for consistency, value and shelf life.

Plenty of Americans come back from Europe convinced they’ve cracked the code to eating bread without regret. They’ll rave about croissants in Paris or focaccia in Florence and swear they had no bloating, no fatigue, none of the stomach drama they expect from a sandwich loaf at home. Social media is full of stories of people eating pizza and pasta every day in Italy and walking away with zero discomfort. The question is whether European bread really is different or if the setting just makes it feel that way.

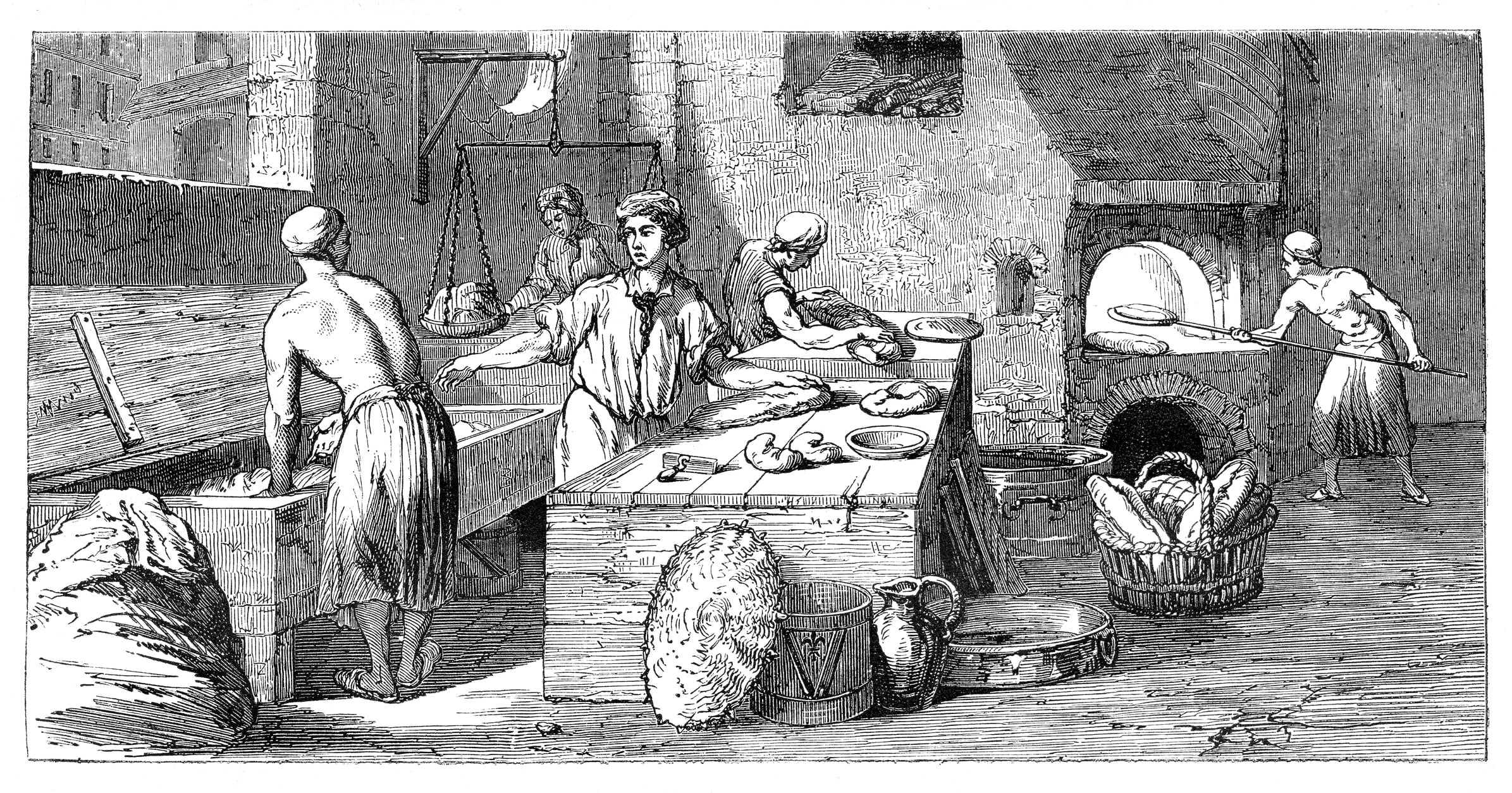

There’s mounting evidence the difference is real. Traditional sourdough fermentation – a cornerstone of European baking – alters wheat’s structure in ways that improve digestibility. American flours and production methods, by contrast, favor speed and shelf life, often at the expense of gut comfort.

Regulation also plays a role. European rules cut out many of the additives and bleaching agents still legal in the US. That leads to loaves with shorter ingredient lists and, many argue, fewer hidden triggers for digestive upset. For consumers, that difference is obvious when comparing a simple baguette to a plastic-wrapped sandwich bread.

Culture ties it together. Europeans are used to buying bread daily, often from local bakeries, and eating it fresh. Americans, by contrast, rely on sandwich bread for its consistency, affordability and week-long shelf life – qualities that make it indispensable in many households. Those opposing priorities shape loaves that not only taste different but can feel entirely different once they hit the stomach.

The gluten and FODMAP breakdown

The wheat itself is a big part of the story. The US mainly grows hard red wheat, which is high in protein and gluten. That’s great for building strong dough and lofty loaves, but the higher gluten load can be tough for people with mild sensitivities. Softer wheat varieties dominate in Europe, producing flour that’s lower in gluten and closer to what you’d find in a baguette than a US sandwich bread.

Fermentation adds another crucial layer. Unlike the quick-rise yeast breads common in US factories, many European baguettes and boules undergo long fermentation. A 2025 review in Microbiology Research found that sourdough fermentation driven by lactic acid bacteria breaks down gluten proteins and reduces FODMAP carbohydrates – compounds that are notorious for triggering IBS-like symptoms.

Other studies back this up. One published in Food Research International showed sourdough fermentation can cut FODMAP levels, including fructans, by 30% or more. Another found rye and wheat doughs lost between 76% and 97% of their FODMAP content depending on the bacterial strains used. Those reductions are significant for people who report bloating or discomfort after standard bread. While celiac sufferers still can’t tolerate sourdough made with wheat, for the much larger group with sensitivities, the science suggests baguette-style fermentation really does matter.

The acids produced during long fermentation don’t just help digestion. They also deepen flavor and slow staling, extending freshness naturally. That’s why a baguette is best eaten the day it’s baked, while sandwich bread is built to last a week with help from preservatives.

Softer wheat, cleaner fields

Differences start even earlier, on the farm. European farmers grow a wider variety of wheat strains, often lower in gluten than the hard reds common in the US. This doesn’t eliminate digestive problems altogether – rates of celiac disease are virtually identical in both regions – but it does shift the average gluten content in flour.

Agricultural practices also diverge. In the US, some wheat farmers use glyphosate as a pre-harvest drying agent, which can leave trace residues. The European Commission explicitly prohibits using glyphosate this way. Regulators in both regions say residues are below harmful levels, but to consumers scanning the headlines, the idea of ‘glyphosate-free’ bread has marketing power. That sense of a cleaner product is part of why a baguette may feel lighter than a slice of sandwich bread.

Rules of the loaf

Look closely at the ingredient label and the contrasts sharpen. A US sandwich bread can list more than a dozen ingredients: enriched flour, soybean oil, high fructose corn syrup, mono- and diglycerides, calcium propionate, dough conditioners, bleaching agents. By contrast, many baguettes are still just flour, water, salt and yeast.

The reason isn’t tradition alone – it’s regulation.

Potassium bromate is still legal in the US as a flour improver, though many bakers have voluntarily removed it. The EU and UK banned it in 1990 because of its links to cancer in lab animals.

Azodicarbonamide (ADA), once used widely as a dough conditioner in the US, has been banned in Europe for more than a decade. Public campaigns in the US pushed some companies to drop it, but it remains legal federally.

Flour bleaching agents like chlorine dioxide and benzoyl peroxide are allowed in the US but prohibited in Europe and the UK. European flour is left to age naturally.

Propylparaben, a preservative linked to endocrine disruption, has been banned in Europe since 2006 but has appeared in some US baked goods.

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is common in sandwich bread to boost softness and sweetness. European bakers rarely touch it.

The EU follows the precautionary principle: if there’s uncertainty about safety, the additive stays out. The US system is the opposite. Through the GRA (generally recognized as safe) loophole, companies can approve new ingredients for themselves without FDA notification. Consumer advocates argue this has left sandwich bread packed with processing aids that Europeans would never permit in a baguette. Still, those same aids have enabled large-scale production of a loaf that millions of Americans can afford and depend on every day.

That doesn’t mean Europe is additive-free. A standard French baguette may contain enhancers and the UK’s high-speed Chorleywood process leans heavily on enzymes and processing aids. But the baseline is different: European consumers expect shorter ingredient lists and the average baguette reflects that.

US vs European bread

| Factor | US sandwich bread | European baguette |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat type | Mostly hard red (higher gluten) | Mostly soft wheat (lower gluten), blends vary |

| Fermentation | 1-2 hours, commercial yeast, dough conditioners | 12-48 hours, sourdough or slow yeast |

| Additives | Bromate, ADAm propionates, HFCS, bleaching agents allowed | Many banned (bromate, ADA, bleaching), HFCS rare |

| Regulation | FDA permits unless proven harmful; GRAS loophole | Precautionary principle; bans on suspect additives |

| Shelf-life focus | Designed to last a week or more | Fresh daily; expected to stale quickly |

| Consumer culture | Pre-sliced, plastic bag, sandwich-heavy | Bakery loaves, smaller portions, mealtime staple |

Bread, culture and freshness

Science and regulation only explain part of the story. Culture fills in the rest. In Europe, the baguette is bought fresh, often daily, from local bakeries. It’s expected to stale quickly, so there’s no need for preservatives to stretch its life. In the US, sandwich bread is engineered for softness and longevity, packaged in plastic and designed to sit in pantries for a week.

Eating styles differ, too. Europeans often eat bread as part of a meal – a roll with soup, a slice with cheese – rather than building giant sandwiches. Combined with smaller portions and a walking-heavy lifestyle, that makes the baguette feel lighter than sandwich bread.

Of course, it isn’t as simple as baguette good, sandwich bread bad. Industrial loaves are common across Europe, while the US has a thriving artisan scene turning out long-fermented sourdoughs that rival any boulangerie. And sandwich bread itself has a social value – it’s cheap, easy to store and feeds families who might not have a bakery around the corner. The real distinction isn’t where the bread is made but how.

Why both baguettes and sandwich bread matter

On balance, the baguette often stacks up lighter than US sandwich bread: softer wheat; long fermentation that reduces gluten fragments and FODMAPs; and stricter controls on additives all tilt the scales. These differences help explain why many Americans feel better eating it.

But that doesn’t mean sandwich bread is ‘bad’. Quite the opposite – it’s one of the most democratic foods on the shelf. Packaged sandwich bread is inexpensive, widely available and plays a vital role in diets, especially for families who need convenience and value. For school lunches, quick breakfasts and everyday affordability, it delivers in ways a crusty baguette never could.

The real distinction is how bread is made. When US bakers invest in longer fermentation and cleaner labels, they can deliver loaves that combine the accessibility of sandwich bread with some of the digestibility benefits consumers associate with Europe. That’s where the opportunity lies – not in ditching sandwich bread, but in evolving it.

Marking a decade of #SourdoughSeptember

2025 marks the 10th anniversary of the Real Bread Campaign’s #SourdoughSeptember, created to celebrate genuine sourdough and the craft of traditional breadmaking.

“Over decades in the UK and countless generations elsewhere, custodians of the craft have built up the reputation of sourdough as offering a route to better-bred bread,” said Campaign coordinator Chris Young. “Many people simply enjoy eating well-made genuine sourdough bread, with some also reporting they benefit from digestive or other health reasons.”

The international celebration encourages people to bake their own sourdough at home, buy it from local Real Bread bakeries and support the Campaign’s charitable work. This year also features resources for children such as the free Dough Monsters care guide and Bake Your Lawn grow-a-loaf booklet. Other activities to watch out for include bread-making workshops, starter giveaways and pizza evenings: find details on the Real Bread’s calendar and social media platforms.

Studies:

Hernández-Figueroa RH, López-Malo A, Mani-López E. Sourdough Fermentation and Gluten Reduction: A Biotechnological Approach for Gluten-Related Disorders. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(7):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16070161

Richa A, Anuj K.c. Unlocking the potential of low FODMAPs sourdough technology for management of irritable bowel syndrome. Food Research International. 2023; 173(2): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113425

Pitsch, J, Sandner, G, Huemer J, et al 021). FODMAP Fingerprinting of Bakery Products and Sourdoughs: Quantitative Assessment and Content Reduction through Fermentation. Foods. 2021; 10(4). httsp://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040894

Kurokawa Y, Maekawa A, Takahashi M, Hayashi Y. Toxicity and carcinogenicity of potassium bromate - a new renal carcinogen. Environ Health Perspect. 1990 Jul;87:309-35. https://doi: 10.1289/ehp.9087309