Key takeaways:

- Slow fermentation delivers better flavor, digestibility and shelf life, giving artisan bakers a clear edge over industrial bread.

- Combining scientific precision with traditional methods helps bakers achieve both consistency and stronger storytelling.

- Collaboration across baking, research and even design shows how bread can move beyond commodity to culture and community.

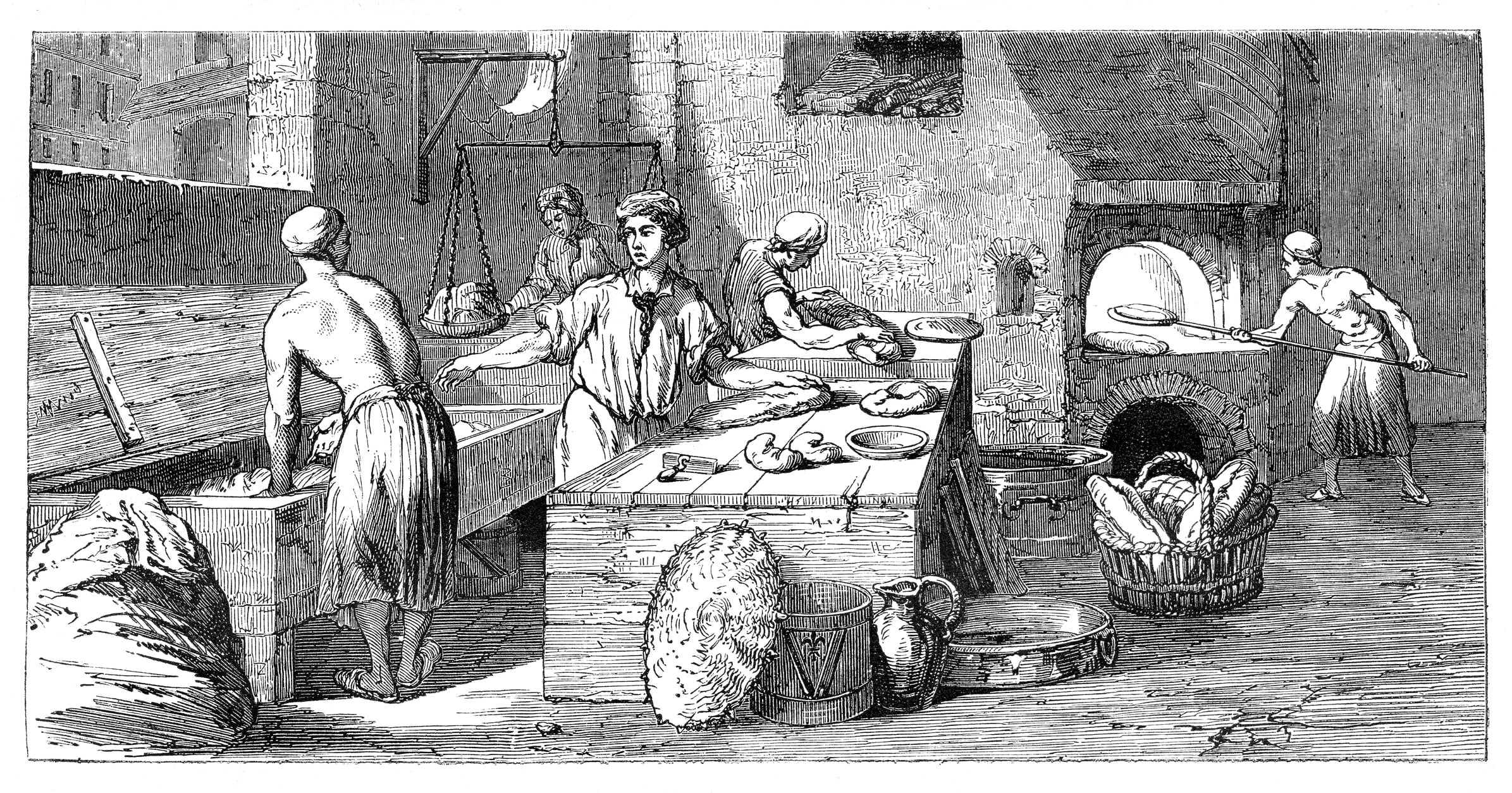

Bread may be one of the oldest foods we have, but it’s also one of the easiest to take for granted. In many markets it has become just another commodity, shaped by speed and efficiency. And yet, around the edges, a different story is unfolding – one that leans into long fermentation, heritage grains and loaves with genuine character. It’s within this shift that the relatively new title of bread sommelier has taken root.

Globally, fewer than 300 people have earned the certification. Only one of them represents Poland: Aleksandra Bednarek. Born in Łódź and now based in California, she runs her own bakery while championing bread as both product and cultural touchstone. Earlier this year, she returned to Poland – not just to visit, but to bake, collaborate and help open up conversations about what bread could be.

Her visit sparked interest from researchers, bakers and even designers. “I’ve always had customers who valued my breads for their organic flour and long fermentation,” she says. “But the sommelier title gave me a new platform. Suddenly I was being asked to teach, to judge, to explain bread in a different way. For me, success isn’t measured only in sales. It’s about changing how people think about bread.”

From Łódź to California – and bees in the backyard

Bednarek’s loaves feel familiar to anyone who grew up with traditional Polish bread: wholegrain, sourdough, seeded. But there’s also a Californian twist: honey. And not just any honey – the kind that comes from hives in her own backyard.

“Beekeeping is my second passion,” she says. “It actually has a lot in common with baking. Both need patience. Both rely on fermentation. And both force you to respect natural timing. Honey changes every season – sometimes dark and treacly, sometimes light and creamy. Customers love that unpredictability. It shows them food doesn’t have to be uniform to be good.”

This theme carried into her summer in Poland. At the Sadkiewicz Institute in Bydgoszcz, she baked with educator Czesław Meus, using spelt, emmer and einkorn from an organic mill. Meus introduced her to the hydrothermal method: soaking part of the grain at 24°C (75°F) for 20 hours before adding it to a chilled levain.

“The dough was extraordinary,” Bednarek recalls. “Soft, elastic and it produced bread that stayed fresher for longer. It reminded me that even after years of baking, there are techniques still waiting to be rediscovered. For bakers, that’s exciting – it means there’s always room to push further.”

She also joined discussions with Prof Kazimierz Sadkiewicz and Dr Józef Sadkiewicz on flour testing and fermentation monitoring. “What stood out was how well tradition and science can work together,” she says. “Using precision tools doesn’t replace craft – it helps us understand and refine it.”

Why slowing bread down matters

At Aleksandra’s Bakery in California, Bednarek works deliberately. She mills at least 20% of her flour fresh every day, often using kamut, einkorn or emmer. Her pan breads are regularly 100% wholegrain, enriched with pumpkin, flax, sunflower or oats pressed inhouse.

Her timeline is long by design. “Two or three days for a loaf is normal for me,” she says. “I start with soaking. I finish with a long, cold fermentation. That’s when everything comes together.”

She explains it in both sensory and technical terms. “Slow fermentation breaks down phytates and lectins, lowers glycaemic response, extends shelf life naturally and develops a deeper aroma. Customers can taste the difference – and they feel the difference, too. That’s why it’s worth the time.”

For her, fermentation is more than technique. “It’s also strategy. In a market dominated by industrial bread, slowing down is how artisan bakers stand out. It builds loyalty, it justifies the higher price point, and it gives you a story to tell that connects with people.”

Three bread cultures

Bednarek’s perspective comes from working across three bread landscapes.

“In Germany, bread is culture,” she says. “The variety is astonishing and customers know exactly what they want. But even there, chains are squeezing independents. It shows that heritage isn’t enough – you have to innovate while keeping your roots.”

Poland, she says, is in a very different place. “You can feel the energy. Especially in big cities, more bakeries are opening and people are asking new questions – about sourdough, about fermentation, about flour. Ten years ago, that curiosity wasn’t there. Now it is and that’s a huge opportunity for artisan bakers.”

California, meanwhile, is sharply divided. “On one side, you have the cheapest industrial bread. On the other, a thriving artisan scene where process and provenance matter. The interesting part is how willing Californians are to pay more for a product that reflects their values. That creates real space for premiumization – but it means bakers have to be transparent and consistent.”

Collaboration as catalyst

Collaboration, Bednarek insists, is what gives the bread sommelier role real life. “At the Sadkiewicz Institute, working side by side with bakers and scientists, you could feel the energy. Everyone brought something different. That’s how the industry grows – when knowledge is shared.”

In Saxony, she worked with master baker and fellow sommelier Stefan Richter. “We milled grain until late at night, tested fermentations, then sold the breads the next morning. Customers loved them. It proved what we know instinctively – quality is recognised immediately. For bakers, it’s reassurance that the investment in skill and time pays off.”

She’s also partnered outside the baking world. In Berlin, she met Maciej Chmara and Anna Rosinke, who run Living a Good Life with Bread, a project that frames bread through art and design. “That really struck me,” she says. “Bread isn’t just nutrition – it’s ritual, memory, even creativity. Those perspectives help elevate bread beyond commodity.”

The bread sommelier title – and why it matters

Globally, the number of bread sommeliers is still small – under 300, with just 26 women. The certification, created in 2015 at the German Baking Academy in Weinheim, runs nearly a year and covers sensory analysis, fermentation science, milling and grain knowledge.

Bednarek sees clear value for the trade. “It’s like learning a new language,” she says. “You can describe a loaf in ways that make chefs, bakers or even customers curious before they taste it. That creates value – because it positions bread not as filler, but as a crafted product in its own right.”

Interest is climbing, particularly from Asia and North America. Bread sommeliers now sit on competition juries, reinforcing their role in shaping standards. “It’s still niche,” she admits. “But every year it grows, and every year it helps strengthen the professional conversation around bread.”

Guidance for aspiring bakers

Although Bednarek’s bakery is in California, her return to Poland has left a mark. She’s been invited to judge the Master Baker competition and to teach at the Academy of Classical Baking in Bydgoszcz. She’s also joined Polska Ekologia, which advocates for organic food and artisan producers.

Asked what advice she would give to those entering the field, Aleksandra doesn’t hesitate. “Bake with integrity. Don’t just follow trends. Understand your ingredients, respect the process, and stay humble. Customers can spot honesty – it’s what keeps them coming back.”

She emphasizes the importance of education. “Take every training opportunity. Learn the science as well as the craft. The more you can combine both, the stronger your position will be.”

And collaboration, again, is her parting note. “Work with others. Share what you know. Our industry only grows when we’re connected. Bread is memory, nourishment and community. If you hold on to that, you’ll do more than sell loaves – you’ll help keep bread at the center of people’s lives.”