Key takeaways:

- ABF is close to buying Hovis for £75m.

- The deal could dethrone Warburtons as market leader.

- Cost-cutting is key as both brands battle losses.

Associated British Foods (ABF) is on the brink of a deal that could rewrite the pecking order of Britain’s bread aisle and put serious pressure on Warburtons’ long-held dominance.

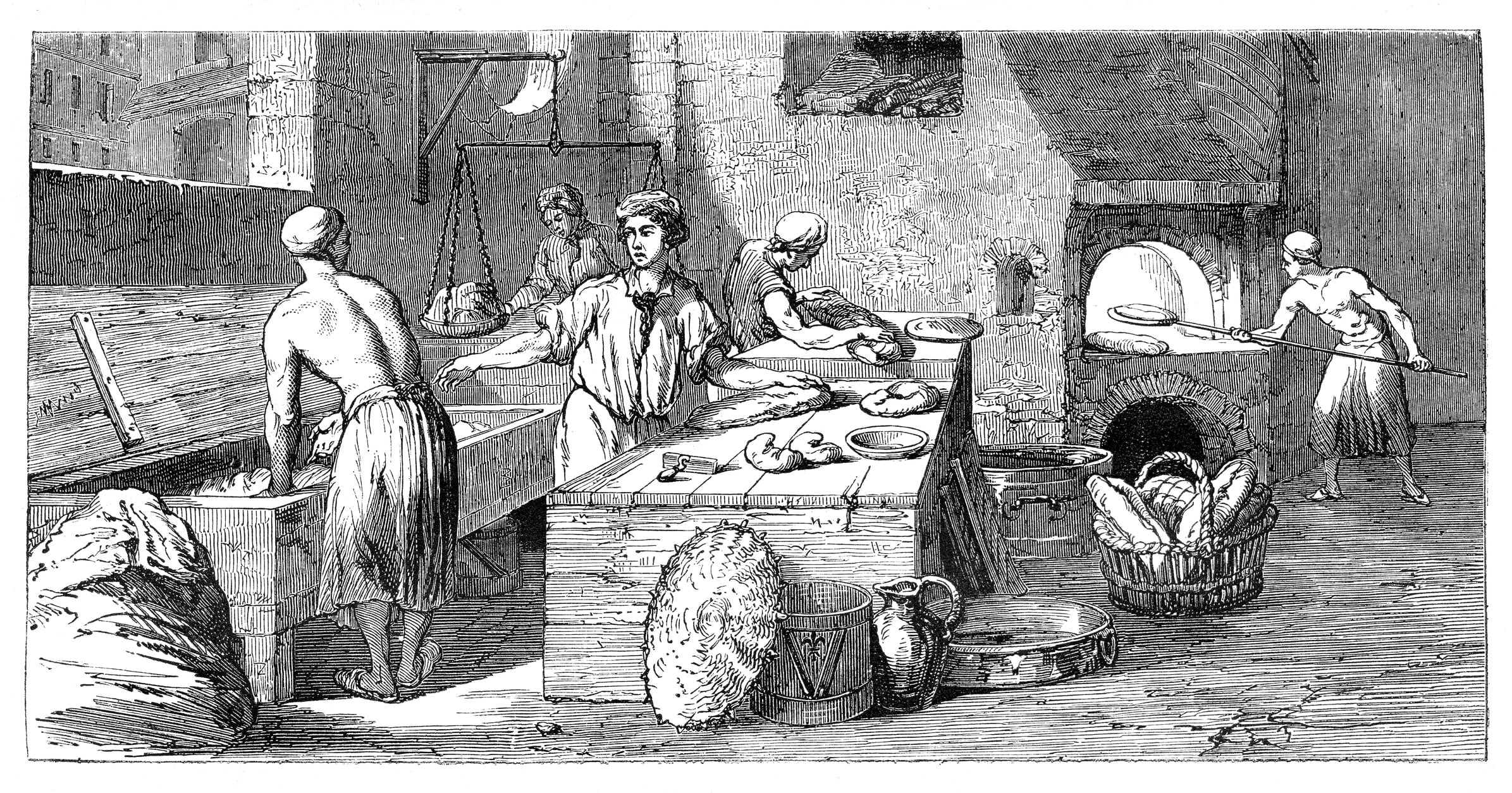

Sky News reports ABF is preparing to acquire 135-year-old Hovis from Endless LLP in a transaction valued at £75 million. No formal announcement has yet been made, but industry insiders suggest the deal is “oven-ready”, with final due diligence and regulatory preparations underway.

If it lands, the deal will unite Kingsmill and Hovis, the UK’s number two and three wrapped bread brands, creating a force large enough to threaten market leader Warburtons – and trigger serious scrutiny from the Competition and Markets Authority.

But this isn’t a celebration. It’s a salvage job. Both Kingsmill and Hovis have been losing ground, customers and relevance.

And while a merger might bring scale, synergy and savings, it also raises a bigger question: can two struggling brands rise together or will they just sink faster?

The £5bn bread basket

Yes, the headline deal value is £75 million, but the battlefield is far larger.

The UK packaged bakery market is worth around £5 billion annually, with the equivalent of 11 million loaves sold each day. That includes everything from everyday sliced loaves to premium sourdough, morning goods and bake-off lines.

And while private label dominates much of the volume, brands still matter – especially in retail positioning and consumer loyalty.

That’s why ABF’s rumored move to consolidate two of Britain’s best-known bread brands is more than just a tidy bolt-on. It’s a full-blown land grab.

Hovis, under Endless LLP ownership since 2020, has struggled to recover its former luster. Pre-tax losses widened to £4.7m in its latest financial year, with turnover dropping to £446.8m. Its last profitable stretch is now a distant memory.

Allied Bakeries, which houses Kingsmill, Allinson’s and Burgen, hasn’t fared much better. The division has consistently underperformed within ABF’s broader Grocery portfolio. In its April results, ABF flagged Allied’s persistent challenges and confirmed it was “evaluating strategic options.”

A merger makes sense on paper. Together, Hovis and Allied Bakeries could strip out duplicate costs, streamline manufacturing and strengthen their retail negotiation power – especially as they lose space to Warburtons and private label rivals.

Industry estimates cited by Sky News suggest the combined group could extract £50m in annual cost savings from a rationalized footprint. But how much reinvestment will be needed to modernize the offer? That’s where things get less clear and far riskier.

Too big to bake? Why regulators may step in

Any deal of this scale won’t go unnoticed by the CMA. Combining Kingsmill and Hovis would effectively consolidate Britain’s number two and number three players – giving ABF an estimated 35%-41% share of the branded wrapped bread market. Warburtons currently holds about 34%, depending on the data source.

Once private label and wider baked goods are factored in, ABF’s post-deal share could fall closer to 14% versus 24% for Warburtons. But in a shrinking category already dominated by a few giants, that’s still enough to raise red flags.

Some analysts speculate the CMA may consider the “failing firm” defense – an argument that reduced competition is permissible if one party would otherwise collapse. That’s been used in other grocery and dairy cases, but it’s a high bar and rare for a publicly listed company like ABF to pursue.

In short, approval isn’t guaranteed. But the timing might help. The current regulatory mood, especially under a new government promising to unlock growth, may be more flexible than in years past. Still, it’s a gamble.

For many in the food and drink sector, this deal was a long time coming.

“The Hovis-Kingsmill merger is a clear sign of the pressures facing the UK bakery sector,” said James Watson, UK partner at transformation consultancy Argon & Co. “With inflation driving up costs and bread consumption in steady decline, consolidation was always a question of when, not if.”

He added that while the tie-up creates a new market leader on paper, “both businesses have been making unsustainable losses. The real prize here is efficiency - rationalizing overlapping bakery networks and cutting costs in procurement, logistics and manufacturing.”

Watson noted the deal fits a broader pattern across food and drink: “M&A is being used to counter cost pressures and capture growth in more resilient categories. The Hovis-Kingsmill tie-up now joins a growing list of strategic pairings, including Mars-Kellanova and Greencore-Bakkavor. The race is on to adapt – and survive.”

But it won’t be easy. “Execution will be everything,” Watson said. “Disrupting existing customer relationships now, while both brands are losing share, would risk compounding the problem.”

What comes next - if the dough rises

As of today, ABF hasn’t made anything official and sources caution that timelines could still shift. But the signals suggest this deal is nearly baked.

Once the ink dries, attention will turn to the integration – and that’s where it gets messy. Rationalizing bakeries could mean site closures. Aligning SKUs could mean shelving brands. A shared sales team may mean tough choices for customers loyal to one label over the other.

ABF hasn’t yet confirmed whether it will retain all four brands – Kingsmill, Hovis, Allinson’s and Burgen – or restructure the range. But analysts say simplification is inevitable if the merged group wants to stay lean.

The bigger risk? That nothing really changes and the combined group simply carries forward the same structural issues that brought both bakeries to the brink.

The UK’s bread market doesn’t need more players. It needs better ones. That’s the bet ABF is making: that scale can buy relevance and that cost-cutting can buy time.

But if the deal falls flat – or if the CMA blocks it – both Hovis and Kingsmill could be left weaker, not stronger.

Either way, Britain’s bread aisle is about to face its biggest shake-up in years. And for Warburtons? The real work to stay ahead may just be starting.