Küllüoba bread has been brought back to life by modern bakers after archaeologists uncovered a remarkably well-preserved example at an Early Bronze Age site.

Packed with ancestral ingredients like emmer wheat and lentils, the bread has gone viral – not just for its deep history, but also for its nutritional punch.

Roughly 12cm across and pancake-flat, the original loaf was dug up last year during excavations in Eskişehir province. After scientists examined the charred remains, they collaborated with local bakers to recreate the recipe and the results have exceeded expectations.

Turkish consumers are queuing up to taste it and the story has received widespread media attention – both in mainstream outlets and across social media. The revival has struck a chord, not only because of its ancient roots but also thanks to its link to ritual, sustainability and rediscovered grains.

For today’s bakery brands, it’s a compelling reminder that when a product’s story resonates emotionally, it can drive real consumer engagement.

Unearthing the past

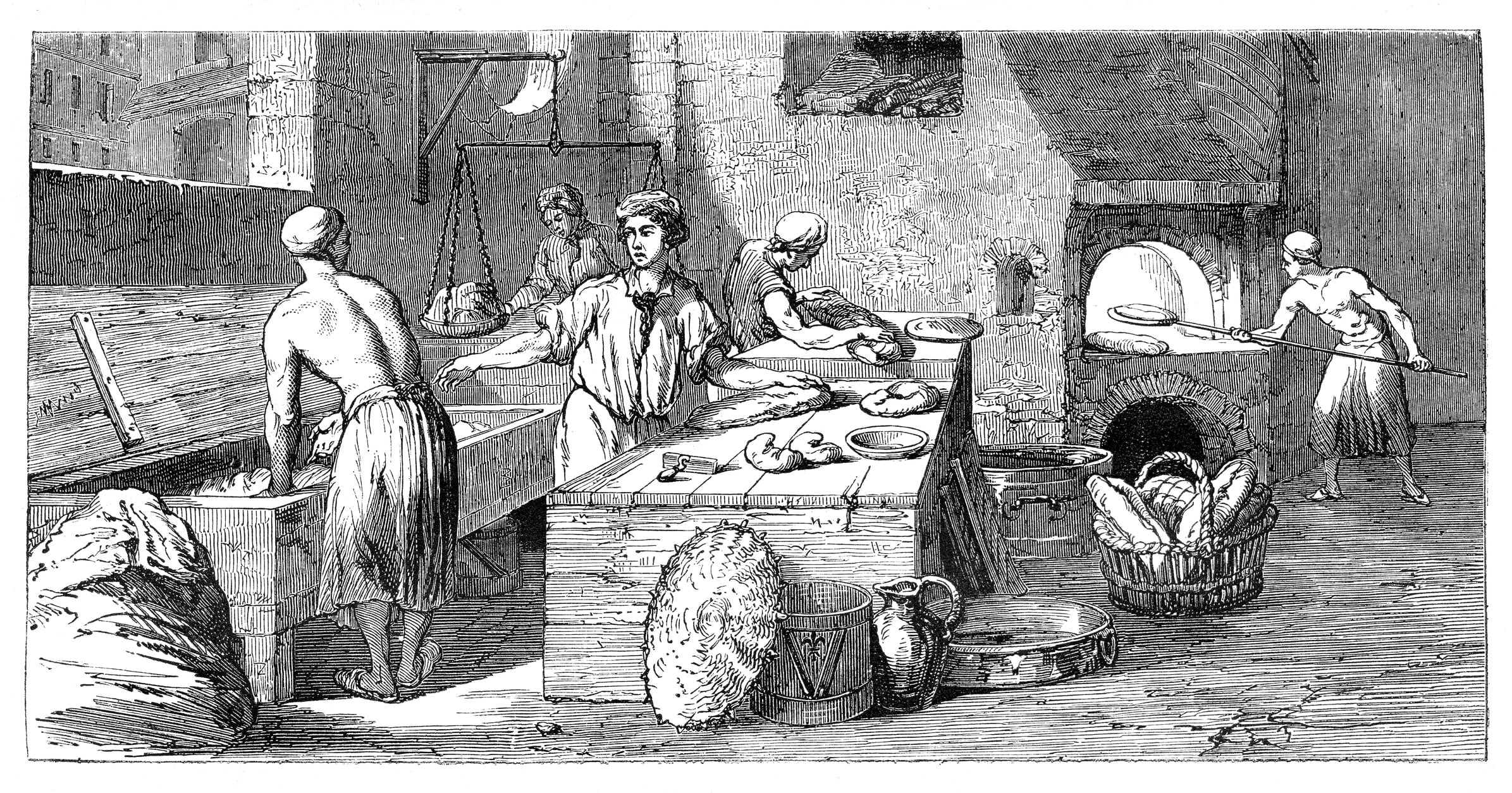

In September 2024, a team led by Prof Dr Murat Türkteki from Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University discovered a charred loaf buried beneath the threshold of a rear room at the Küllüoba Höyük dig site, located in Western Central Anatolia. Radiocarbon dating traced the bread back to around 3300 BCE.

“This is the oldest baked bread to have come to light during an excavation and it has largely been able to preserve its shape,” Prof Türkteki told Agence France-Presse (AFP). “Bread is a rare find during an excavation. Usually, you only find crumbs.”

In this case, a piece of the loaf had been torn off, intentionally scorched and buried under red-coloured earth at the entrance of the home. This suggests it was used as a symbolic or spiritual offering – perhaps to promote fertility or safeguard the household. It is rare but meaningful evidence of Neolithic rituals that revolved around food.

“The bread’s carbonisation and burial demonstrate ritual use, possibly related to prosperity and protection,” said Prof Türkteki.

Microscopic analysis revealed the bread was made from a blend of coarsely ground emmer wheat - locally known as ‘gernik’ – with lentils and a leaf from an unidentified plant that may have helped to leaven the dough.

The bread was fermented and baked, resulting in a crisp outer crust and a soft centre – proof that Bronze Age bakers knew their dough when it came to technique.

The ancient bread’s burnt remains are currently on display at the Eskişehir Archaeological Museum, located in the heart of the city.

Modern revival

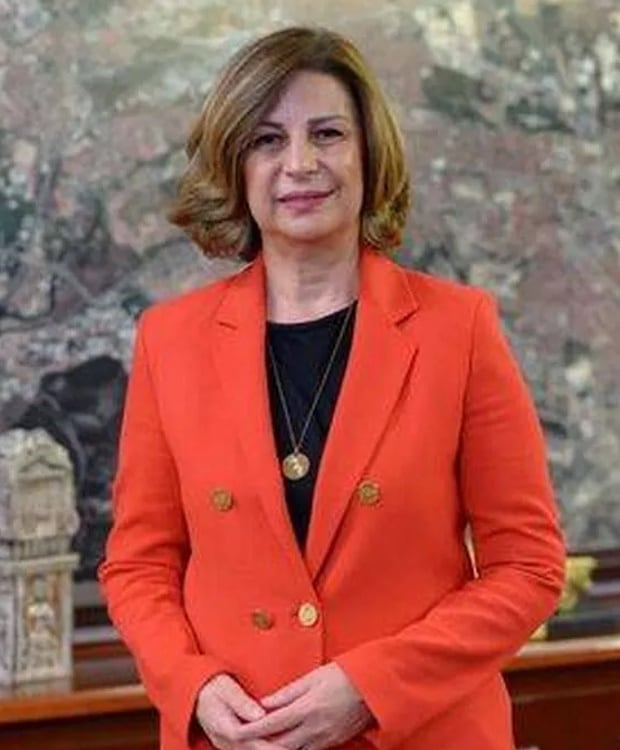

When Eskişehir’s mayor Ayşe Ünlüce learned about the find, she was immediately inspired. “We were very moved by this discovery,” she said. “Talking to our excavation director, I wondered if we could reproduce this bread.”

And replicate it they did. Working from the lab analysis, the Halk Ekmek Factory rolled out a modern version of Küllüoba bread, now sold in local markets for 50 Turkish Lira (about $1.28). The loaf is reminiscent of fresh Turkish flatbreads like bazlama – typically cooked in a pan or outdoor oven and known for its soft, fluffy texture.

Other beloved flatbreads in Türkiye include pide, a larger, oval-shaped bread often topped or filled with savoury ingredients such as minced meat or spinach; and lahmacun, a thin, crispy bread frequently dubbed Turkish pizza, topped with a seasoned meat mixture.

Bread plays a central role across the Balkans and is eaten daily in various forms – from small rolls to sesame rings and flat, pan-fried rounds.

Since ancient emmer seeds are hard to come by in Turkey, the manufacturer opted for its close cousin kavilca wheat. This is blended with bulgur and lentils to mirror the original mix. The resulting 300g loaf stays true to form: flat, round and about 12cm wide. Like its ancestor, it’s fermented and baked at around 150°C (302°F).

“The bread is made by combining ancestral wheat flour, lentils and bulgur, which results in a rich, satiating, low-gluten, preservative-free bread,” bakery manager Serap Güler told AFP.

Locals are loving it and early batches sold out almost instantly. With its chewy texture, nutty flavour, pale yellow hue and wholesome ingredients, the bread taps into today’s appetite for natural, back-to-basics nutrition.

Lessons from the past

Beyond stirring up curiosity, the Küllüoba bread revival is fuelling a conversation about agricultural resilience. The Eskişehir region – once lush with water – is now dealing with drought.

“We’re facing a climate crisis, but we’re still growing corn and sunflowers, which require a lot of water,” said Mayor Ünlüce. “Our ancestors are teaching us a lesson. Like them, we should be moving towards less thirsty crops.”

Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccum) is one of the oldest cultivated grains, grown in places like Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. It’s a hulled wheat, meaning each grain is enclosed in a tough outer layer that has to be removed. But it’s worth the extra work: emmer is protein-rich, low in gluten and loaded with nutrients. Its flavour is earthy and nutty.

The loaf’s nutritional profile includes B vitamins, antioxidants, dietary fibre and resistant starch that helps regulate blood sugar. Lentils and bulgur add even more fibre and plant protein to the mix. It’s ancient fuel for modern lives.

What can modern bakers learn from this?

Küllüoba bread is more than just a trending artefact. It shows how the power of tradition, narrative and nutritional authenticity can meet the moment in today’s bakery landscape. Here’s what bakers can take away:

- Story sells. A product with a great origin story – especially one involving heritage and rituals – has emotional pull.

- Health is heritage. Ancient grains align with current trends: high in protein and fibre, low in gluten and naturally wholesome.

- Sustainability matters. With climate challenges top-of-mind, grains that need less water offer environmental and marketing value.

- Make it experiential. Offering consumers a ‘taste of history’ taps into curiosity, culture and culinary adventure.

It proves the past still has plenty to teach us about food, resilience and what truly resonates with consumers today.